Dewey Brown (center) at Cedar River Golf Club in the late 1960s, with his son, Roland Brown Sr. (right), and blues musician William “Sweet Willie” Brown (no relation). Photos courtesy of PGA Magazine

Editor’s note: The following story was originally published in the July 2017 issue of PGA Magazine and is reprinted here with permission of the PGA of America.

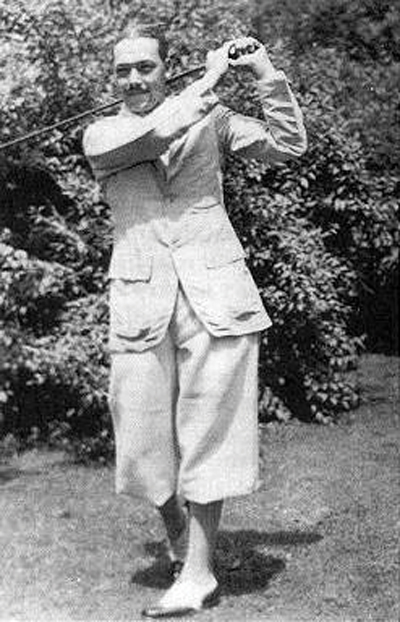

Dewey Brown became a member of the PGA of America in 1928. Twenty-nine at the time and working at what is now The Shawnee Inn & Golf Resort in eastern Pennsylvania, Brown was well-known for his golf skills and Southern gentleman temperament. History, however, recognizes him in a more profound way — as the first African-American PGA professional.

In 1934, Brown’s tenure was cut short when the PGA implemented a Caucasian-only clause, forbidding individuals of African, Native American, Asian or Latino descent from joining the ranks of the PGA.

As historians and Brown’s living relatives tell it, Dewey was a fair-skinned black man and was able to avoid racial discrimination when he initially became a PGA member. Essentially, during a time of accepted racial exclusion, Dewey was able to pass for white and go relatively undetected in Caucasian circles.

“When he joined the PGA, from what we know, the issue of race never came up, because people just assumed that he was white,” says Malakhi Simmons, Brown’s great-grandson. “It wasn’t that he was hiding it, because black people in the area knew who he was. It was more a case of people’s assumptions opposed to him intentionally passing himself off as white.”

Brown may have realized, however, that his career was at stake if his racial background were discovered. A story passed down through his family holds that when he would compete in tournaments, his son would caddie for him. Brown’s son was more noticeably African-American than his father, and thus was not allowed to address him as “father” or “dad” during competition to keep the truth about Brown’s race concealed.

It is speculated that late in 1933, the PGA was made aware of Brown’s racial identity. Coincidentally, the Caucasian-only clause, which came into effect that same year, legitimized the removal of Brown’s membership.

Humble beginnings

Brown’s keen interest in the game of golf began well before those years. He was born in North Carolina in 1899, the son of two Southerners. Both his mother and father were fine dressers and took pride in how they looked — a trait they passed on to their son. His family was better off than most black families of the time, as indicated by the fact that they were landowners in a Southern state. Brown’s polished upbringing was likely a major factor in his success in the golf industry.

When Brown was a child, his family moved to an affluent area of Morris County, N.J., where his father purchased land for the purpose of dairy farming. Newly minted to the north, Brown began working at Madison Golf Club as a caddie, which was where he was introduced to the game that would change his life.

It was the liberal friendship of the club’s Scottish golf professionals who taught him the game and its rules — as well as how to make golf clubs — that put Brown on a path toward success in golf. That path would prove tumultuous, but Brown never strayed, even after his expulsion from the PGA made finding sustained work difficult.

“You see in writing that he was a gentleman of the fairways. He was a gentleman before anything else, and was recognized for that,” says Roland Brown Jr., Dewey’s grandson. “As such, he was hired quite often to fill professional vacancies and voids at clubs around New Jersey, but because he was black, it was only temporary.”

Forging his own way

Unable to find long-term employment because of his race, Brown took matters into his own hands. In 1947, using his savings and some of his family’s accrued wealth, Brown purchased Cedar River Golf Club, a nine-hole course and small hotel in Indian Lake, N.Y., in the center of the Adirondack Mountains. Brown bought the property, which had originally been a stagecoach stop and farmland, from the Indian Lake Civilian Conservation Corps.

The president’s clubmaker and his club: Brown purchased Cedar River Golf Club and the adjoining Cedar River House hotel (above) in 1947. He owned and operated the property until his passing in 1973.

“Cedar River was his love,” says Roland Brown Jr., who, as a child, would work at the course with his sister, Gloria Brown-Simmons, during the summer months, alongside their grandfather. “I started as a dishwasher, and as I aged, I improved my position. I went on to busboy, then waiter, then bartender. In the off hours, I had a little boat and would float up and down the river fishing out golf balls at the fifth and ninth holes.”

In 1957, Brown gained membership in GCSAA, and enjoyed a strong relationship with the association until his passing in 1973. In fact, Brown was buried in the green jacket and tan pants combination that was associated with GCSAA members at that time. According to Craig Smith, former director of communications for GCSAA, Brown is thought to be the first African-American member of the GCSAA.

“One of my favorite stories that my grandfather told me is that when he attended GCSAA meetings, other members would bring him brown paper bags with patches of bentgrass so he could plant them on his greens, which helped him have nine of the nicest little greens in the Adirondacks,” says Roland. “The GCSAA was wonderful to him, and a great outlet.”

In addition to being a knowledgeable greenkeeper, Brown was also an established and sought-after club builder. He even crafted golf clubs for President Warren G. Harding. The Harding Home & Memorial in Marion, Ohio, is currently working with Brown’s family in an effort to identify the exact clubs Dewey made for the 29th president.

“Every golfer has benefited from the first person to play golf, or the person who invented the golf tee, or created a new way to design clubs or engineered a new turfgrass for greens,” says Simmons. “All these things are a part of today’s game and its history. Each player, each PGA member in particular, is connected to every member that’s ever lived and contributed to the association. That’s why my family, and many others, believe it’s so important for Dewey Brown’s story to be told.”

In 1961, the PGA revoked the Caucasian-only clause, and four years later, Brown was reinstated as a PGA professional. “The legacy of Dewey Brown and his place in golf history is very special,” says Bob Booth, the present-day PGA professional at Cedar River. “I take pride in my position at Cedar River, the heritage of the club, and the strides the PGA has taken over the years.”

Tony Starks is an associate editor with PGA Magazine.