Anyone being paid to apply pesticides on property they don’t own — like a golf course — is considered a commercial applicator, and every such property should have at least one licensed pesticide applicator on staff. Photo courtesy of PBI-Gordon

Certifications are not new in the golf course management industry. Superintendents can become Certified Golf Course Superintendents through GCSAA or earn Master Greenkeeper status through GCSAA’s international counterpart, the British and International

Golf Greenkeepers Association. Equipment managers can now become certified through a GCSAA program.

Certification also is relevant to those applying pesticides to golf courses. A certified pesticide applicator or “commercial applicator” is anyone applying pesticides on the property of another for a fee; in other words, if you are being paid

to treat property you do not own — the golf course you work at, for example — you are considered a commercial applicator.

Often a state’s laws are stricter than those of the U.S. EPA, and in most states, the state’s department of agriculture or Extension service is responsible for license testing. Usually testing consists of two exams — a core exam and

a specific category exam, such as turf and ornamental. Most states also require its license holders to have a certain amount of general liability insurance, and this would be paid by the golf course you work for.

In preparing for testing, applicators should have practical knowledge of a pesticide label; pest identification and management; pesticide formulations; laws and regulations; pesticide application equipment; basic calculations; and pesticide safety. Study

guides for the core exam and the category exam can generally be purchased from your Extension service, state department of agriculture, or the state agency tasked with regulating the use of pesticides in your state. In some states, an Extension service

may provide a prep course prior to taking the exam; however, this varies state to state. Some states still have paper exams, but most have added the ability to take a computer-based exam performed at a local technical college or testing center.

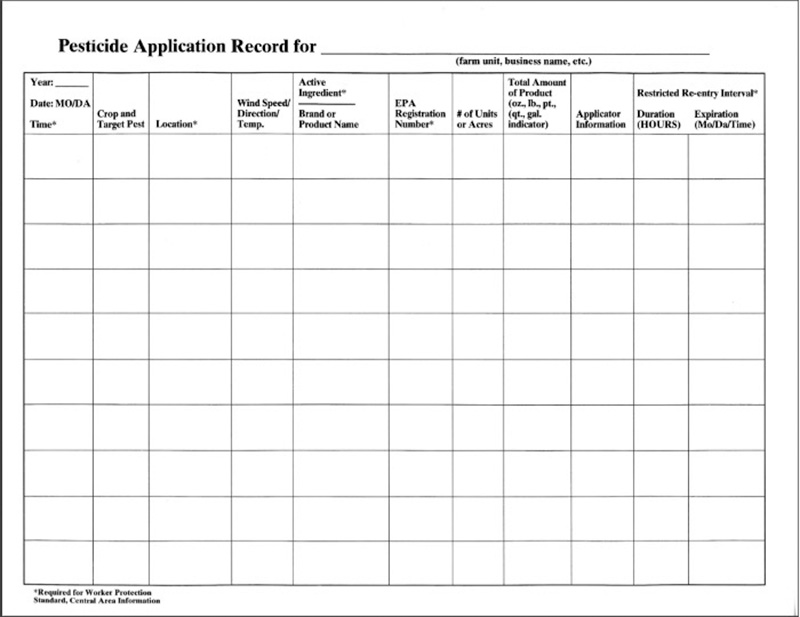

Figure 1. Example of a pesticide record-keeping form.

Points of emphasis

Here are some items applicators need to be aware of once they are licensed:

Continuing education

Applicators will need to attend trainings to obtain continuing education units (CEUs). The number of CEU hours required varies state to state, but in general, the license holder has a period of three to five years to obtain these.

Also, these trainings serve as a way for the applicator to continue learning about pesticides, laws governing them, pest identification, and new sampling and application techniques. Most states require license holders to renew their license annually.

License holders need to make sure their address and contact information are current with the agency that issues the license.

Change of address

If you change jobs or your mailing address, you must notify the agency that issues the license. Remember, it is your license, not your employer’s license. Therefore, the license goes with you.

Record keeping

Pesticide application records must be maintained. This means that for every pesticide application made, you record it — the who, what, where, when, why and how. These records must be maintained for at least two years. I recommend

keeping them longer (Figure 1).

Regulatory inspections

Expect a visit from a regulatory agent who conducts pesticide inspections in your area. Some inspectors conduct inspections every two to three years, but this does vary. During these visits, inspectors will be looking at your pesticide

application records, pesticide storage areas (Figure 2), pesticides used to ensure they are being used properly, etc.

On-site requirements

Only one person per golf course must be licensed; the other employees can work under one license holder, with some exceptions. If you are applying a restricted-use pesticide, then the licensed applicator must be on-site (as per the

label). Also, if your state has direct-supervision laws in place, this means the signal word on the pesticide container will determine how far away the licensed applicator can be from the application site. For example, in South Carolina, any pesticide

used that has the signal word “Caution” requires the licensee supervising the application to be within 100 miles by ordinary ground transportation of the application site and immediately available by telephone or radio (An example of

a full label, for PBI-Gordon’s SpeedZone, can be found here).

Responsible parties

If you become licensed and allow someone working under your direction to apply pesticides, then you are ultimately responsible for the application. Therefore, it is imperative that you conduct in-house training with your staff about

proper pesticide use. If the applicator making the pesticide application is licensed, then they assume the responsibility for the application.

Protect yourself. Wear your personal protective equipment (PPE). The label lists the minimum PPE required. Also, you will be responsible for providing PPE to your staff who apply pesticides as a part of their job.

State sharing

Some states do allow reciprocal licenses, meaning if you obtained a license in one state and relocate for a position at a golf course in a neighboring state, you would have to apply for a license in the neighboring state but not be required

to retake the exam. Being previously licensed, you would fill out an application and pay a fee.

Figure 2. An example of a pesticide storage area. Photo courtesy of the USGA Green Section

Final considerations

Becoming a licensed pesticide applicator plays an important role in demonstrating to your employer you are competent in applying pesticides. However, it also comes with responsibility.

There is a certain knowledge base and skill set needed before one can feel comfortable making pesticide applications. If your course currently has a licensed applicator on staff, then look for an additional employee or two who have an interest in becoming

licensed. I recommend more than one person becomes licensed. The main reason for this is, if a licensed applicator leaves, is on vacation, or off for any extended period, then there is still another one on staff.

So, look at your current operation, and if you or one of your employees are ready to become licensed, start out by contacting your state agency responsible for pesticide licensing (in most states, that’s the state department of agriculture) or your

Extension service. Ask what steps are needed to become licensed.

One final consideration: If you are currently making pesticide applications and are not licensed, stop making those applications and take the time to become licensed. The potential fine and professional embarrassment will cost more than the license.

Joshua Weaver, Ph.D., (jrw0096@auburn.edu) is an assistant professor of horticulture at Auburn University in Auburn, Ala. He is a current GCSAA grassroots ambassador and a former state pesticide inspector in Georgia and South Carolina.