The majority of the crew members who maintain Hilaman Golf Course — located in the heart of Tallahassee, Fla., and operated by the city — are part of a work-release program aimed at setting inmates up for success post-incarceration. Their employment at the course often lays the groundwork for a better path forward. Photo courtesy of Hilaman Golf Course

It’s easy to spot the newest members of the work staff at the two municipal golf courses in Tallahassee, Fla. Even after they’ve traded their prison-issue light-blue work uniforms for civilian dress, they tend to stand out.

“They’re all real well behaved,” says Phil Patterson, a five-day-a-week golfer at the 18-hole Hilaman Golf Course. “When they first get out there, they still have their prison face on. After a month or so, they learn to smile and wave and say ‘Hi’ again.”

There’s far more to it than simple pleasantries and minding of manners. For nine years, Hilaman and the nine-hole Jake Gaither Golf Course have served as a crucial part of a work-release and reentry program for former offenders. In fact, the courses’ nearly entire part-time staff comes from the Second-Chance Program — and some of the full-timers are program graduates.

“It’s been good for us,” says Shane Bass, CGCS, a 26-year GCSAA member and superintendent of golf maintenance for the city of Tallahassee who has been at Hilaman for three years. “It has its challenges, but it’s so rewarding. You take guys who sometimes have nothing, who had something bad happen to them. Sometimes you’re taking guys who were kids, who never had a job, who went right out of high school and went into the system. They don’t understand work. It’s good when you see guys like that come in, work hard and go on and do their own thing.”

Most of them do just that. More than 500 men have gone through the program, and 75 have been hired in city departments alone since their release. The program also touts a 70% “success” rate.

And just what counts as a success?

“Success is not back in prison,” says Jan Auger, the city’s general manager for golf courses, a huge proponent of the program and a key reason behind its success. “A lot of these guys just need somebody to care about them, to be good role models, but also to put them in their place when it’s needed. I was talking to one of the guys, and I said, ‘Don’t mistake kindness for weakness. I’m not stupid. I’m trying to show you respect. It’s up to you. I’m not going to coddle you. If you’re not going to work, if you’re not going to make the most of this opportunity, I’m moving on.’”

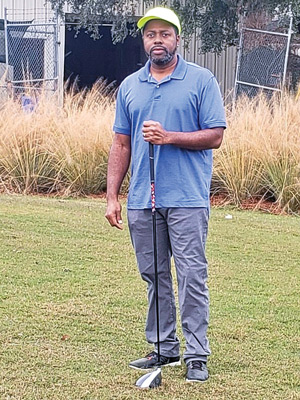

Olando Thompson

Though it’s labeled the Second-Chance Program, that’s a bit of a misnomer in the case of Olando Thompson. It could be argued this is really only his first chance.

A native of Jamaica who moved to the U.S. at 14, Thompson was incarcerated at 18. He spent 10 years in prison, and because his record included a gun charge, his options were limited. Generally, the Florida Department of Corrections won’t approve work release for some prisoners — sex offenders, violent criminals, repeat offenders or those with gun charges.

Thompson so impressed Auger during his first stint at Hilaman in the restrictive first phase of the program that she wrote a letter of recommendation. The city granted an exception. “Jan sticks her neck out for you,” Thompson says.

And Thompson wasn’t about to let her down. After his transfer to the Tallahassee Work Release Center, he returned to Hilaman — in street clothes, not the light-blue prison uniform — and went to work.

“When I started out, I worked hard,” he says. “I made sure I was there on time, made sure the work was done the proper way. I made sure everything I did, I did with precision. Jan saw that, and she asked me if I was going to stay in Tallahassee when I got out. I said yes, and she helped me get the job I’m at now.”

During his time at Hilaman leading up to his release in April 2021, Thompson eventually was entrusted with just about every task there, inside and out. The first time he set foot on any golf course was his first day at Hilaman in 2019.

“I’d blow the course, cut grass, cut tees, cut greens, help with aerifying — that’s when you basically destroy the green to make it a little better,” Thompson says. “I cut the new holes to put the flag in, and every now and then we might have to cut a few trees down. I’d never done anything like that before, none of it. Everything I know now, I learned there — everything I know, about the golf course, the pro shop, how to operate the mowers, fix the mowers.”

Auger helped create an OPS (Other Personnel Services, basically a temporary full-time/no-benefits job) position at Jake Gaither to keep Thompson around. And she steered him into the city’s commercial driver’s license (CDL) classes. He passed his CDL tests and is in line for a position in the city’s fleet management department and for a grant to attend mechanic school.

“He’s a good person, part of the family,” Auger says. “He doesn’t want to leave, but I told him, ‘No, man, you’ve got to go.’ It’s too good of an opportunity for him. And we’ll slide somebody in his position if we think they want to turn their life around.”

That’s precisely how Thompson views his time in the Second-Chance Program.

“They helped me so much, to get a job with the city and then to get a job when you get out,” he says. “To be honest, it wasn’t so much that I wanted to work at the golf course. They asked, and I said, ‘Sure.’ It was an opportunity. Then I saw how it was, how respectful they were toward us. They treated us like human beings. They talked to us. They let us know there were great opportunities to work on golf courses.

“There’s a saying, ‘You can’t take a horse to water and make it drink the water.’ They’re like that. If you need help, they will help you. But there are things you have to do, too, and you have to work hard. I’d never been in Tallahassee a day in my life before I came here, but I ended up staying because I saw the opportunity. They actually helped me, and they’re still helping me. They let me know they’re always a helping hand if I need it.”

The nuts and bolts of the Second-Chance Program

Participants in the program typically are in the final 10 months of their sentences.

While still in prison, they can apply for work release and join what is called Permanent Party. At that point, they wear their prison uniforms and work under close supervision at sites in and around Tallahassee. They return to their prisons after their shifts.

The next step is a transfer to a work-release center — in this case, the Tallahassee Work Release Center. The participants can wear regular work clothes along with ankle monitors. They’re responsible for finding transportation, typically bus, to and from work at set times and live at the center. Tardiness or leaving work early is treated harshly and can result in removal from the program.

Editor’s note: A partnership with a women’s prison has solved a South Dakota golf course superintendent’s labor struggles and helped inmates’ lives change course. Read more in Unlocked potential: Inmates in golf course maintenance.

Unlike some other states’ department of corrections programs that pay work-release inmates pennies, the Tallahassee program pays Florida’s minimum wage of $10 per hour. But there’s a catch. The state collects 45% of after-tax pay to cover room and board, and 10% can be garnished for restitution or court-ordered payments. Another 10% can be docked for family assistance or child support, and participants are required to save 10% of their net pay. They’re allowed $65 per week for incidentals and must deposit their remaining earnings into their savings accounts.

It’s designed so the graduates will have a small savings upon release. In contrast, offenders who don’t go through work release leave prison with a bus ticket and $100.

Auger, though, wants everybody who goes through the program to take away more than a small nest egg.

“They learn a skill while they’re here,” she says. “We try to push the guys to get their CDLs. When they get their CDLs, it’s like a diploma for them. It’s a big deal.”

Tiant DeWindt

Tiant DeWindt had been on golf courses before he went to work on one, but he wasn’t swinging a club. A young DeWindt, his uncle and cousins would sneak onto a nearby course in his native U.S. Virgin Islands to play ... baseball.

“But I’ve always had a kind of love for the game of golf,” DeWindt says. “Maybe not a love, but an interest in the game from a young age. I used to watch the Masters. But I didn’t get into golf until coming through the Second-Chance reentry program.”

In fact, his first experience trying to play golf likely resonates with countless players.

“The first day I swung a golf club, I was sanding the driving range — filling divots,” DeWindt says. “There was an older gentleman who came out twice a week. We had a conversation. He said, ‘Go ahead. Swing this club.’ I swung and knocked the ball about 175 yards. Ever since, I’ve been trying to reproduce that swing.”

DeWindt says that with obvious glee, but he’s decidedly more serious when he talks about how much the reentry program has helped him. He followed the usual path — working Permanent Party, then work release at Hilaman. There were no openings at either golf course when he completed the program, but he was guided toward various OPS jobs with the city, working his way up from janitor at city hall to maintenance and a position at the bus terminal. When the supervisor at Jake Gaither retired nearly four years ago, DeWindt was hired to replace him.

“I’d say they really took a chance on me,” DeWindt says. “When you’re coming through the reentry program, coming from prison, most people have a negative connotation of you. ‘He’s not a good fit. He’s probably on his way back to prison.’ That’s the general thing people keep in the back of their mind. But Jan and the city never put that up as a derogatory statement toward you. They say, ‘You made a mistake. You went to prison. It’s how you bounce back from that mistake that matters.’

“I could have made a mistake and gone right back to prison. The guys who come through now, they know where I’m coming from. And the ones who go through the program and leave where they’re going, now they have a letter of recommendation from the city, good references. If anybody says, ‘Hey, man, you’ve been to prison. What’s to stop you from going back?’ They can say, ‘I have this letter from the city of Tallahassee. I’m a good worker.’ The opportunity Jan and the city put in front of you is a steppingstone.”

‘There should be more programs like this’

Phil Patterson plays golf at Hilaman every weekday. And every weekday, he brings in coffee for the crew.

“I was a grunt in Vietnam, and we didn’t have a damn thing, except what we needed to do to get the job done,” Patterson says, “so any treat is kind of a big deal, it seems. A cup of coffee in the morning is a big deal with these guys. It struck a chord. I guess I just understand that kind of man. A little bit goes a long way when you’ve got nothing.”

Patterson knows more than most about the men who cycle through the program. He spent his professional career inside the legal system, working as an assistant public defender.

“I dealt with these guys before they went to prison,” he says, “and now I’m catching them on the way out.”

As someone familiar with both ends, Patterson approves wholeheartedly of the reentry program.

“Again, from the perspective of having spent my entire professional career in the criminal justice system, I think it’s great,” he says. “These guys are given a chance to learn, whether it’s fixing stuff, driving the machinery, working on the grass ... and there’s a surprising percentage of people who just take to something when given the chance, who then find a job when they get out, and not just a minimum wage job. I think it’s successful in terms of transferring people from prison into a meaningful, well-paying job. There should be more programs like this. If you go right back to where you came from, you go back to prison. This gives people that chance. There’s a door right there if you choose to walk through it.

“And the fact that it’s at the golf course, I think, helps them transition from lockdown to the street. That’s a huge change in their world. Here, they can ease into it. It’s an easy place to be. Everything is real casual.”

Editor’s note: Working on the maintenance crew at a Maryland golf club has been a source of pride and belonging for employees with different abilities. Read about the club’s partnership with a job placement firm and the tremendous benefits for all parties in Ready, willing and able: Inclusiveness in golf course maintenance.

The odds against former offenders in general are stark. The Harvard Political Review just this year found recidivism — the likelihood of a prisoner being rearrested — in the United States to be 76.6% within five years. That is, more than three of every four released prisoners return to prison within five years.

But it also found that prisoners who are taught valuable skills and hold jobs during their incarceration, if they are provided a fair and equitable wage, are 24% less likely to recidivate.

Proving, in the words of superintendent Shane Bass, CGCS, that “it takes a village,” city of Tallahassee employees turned out in force for recent aerification work at Hilaman Golf Course. That’s Jan Auger, the city’s general manager for golf courses, on the left ProCore, and Raoul Lavin, assistant city manager, operating the one on the right. Photo by Shane Bass

The nonprofit Prison Policy Initiative pegged the pre-pandemic unemployment rate among formerly incarcerated individuals at five times greater than that of the general public. In what it called the first study to quantify that statistic, the Prison Policy Initiative found in 2008 that 27% of formerly incarcerated people were jobless. The peak unemployment rate for all adults during the Great Depression was only 25%.

And when race is factored in, the outlook is worse: At the time of the study, the unemployment rate among Black men in their prime wage-earning years of 35 to 44 was 7.7% among the general population, but 35.2% among the formerly incarcerated Black men of the same ages.

“A lot of these guys don’t have a good support system — or any system at all,” Auger says. “Some of these guys have three, four kids. Their wages are garnished, moms wanting them to step up and take care of their kids. We had a kid come through, a big computer kid. We sent him to computer classes, got him a job working with computers. When he got out, the mother of his kid said she wanted him to support their kid. He said, ‘I can’t even take care of myself.’ But once he got stabilized, he was able to take care of his kid. They got married.

“But there are so many obstacles. It’s so hard. You know how life is — it weighs you down. Imagine if you owe money, can’t get housing, can’t get a job. It’s unbelievable what obstacles they have. We realized these are people, people with dreams, just like me and just like you. They got derailed along the way, made some bad choices. I guess I used to think they chose to be a drug dealer. That’s just the way it is. But I realized that nobody chooses to be a drug dealer. Nobody chooses that. So, let’s try to help them.”

Ahmad Favors

Ahmad Favors doesn’t mince words when asked what his future might have looked like without a second chance.

“I’d probably go back to doing the same things I was doing before,” says Favors, who was incarcerated twice; after the second stint, he took advantage of the reentry program through Hilaman. “Without any skills or anybody to help me, as I got back into society, I would have gone back to doing what I was doing. To be honest, this gives me an opportunity to see bigger and brighter things.”

Favors had heard about the program — and about Auger — from folks at the Tallahassee Work Release Center.

“Once I got here, it changed my life,” Favors says. “It’s a great program, as far as the help and the benefits and the reentry into society.”

Like Olando Thompson, Favors was steered toward his CDL. The two actually studied together, and Favors also passed his CDL tests. He has applied for a job in the city’s beautification department, where he hopes to put his license to use.

“They helped me get my CDL, and they helped me learn how to communicate with people better,” he says. “I learned how to exert myself in different ways.”

Like many others in the program, Favors hadn’t been on a golf course until he started at Hilaman.

“I’d never been on a golf course, never swung a golf club,” he says. “After being here and meeting different people here at Hilaman, I picked up a club. Once I picked it up, I just kept picking it up. I love it. I love the game. That was a great experience for me.”

Favors “graduated” from the Second-Chance Program in mid-December. On his last day, Patterson — the Hilaman regular who brings the crew coffee — brought in doughnuts, too, in Favors’ honor.

‘It’s constant turnover’

Not every tale from the program is a success story. Sometimes participants are found using drugs at the work-release center, Auger says, and they’re returned to prison.

Sometimes the offenses are far less severe — but just as consequential.

“The biggest thing is administrative issues,” Auger says. “We don’t have guys robbing us at gunpoint or anything like that. We had one guy who was really good. He had an extra cell phone. That’s against the rules, so he got sent back to prison. You train ’em, and sometimes they do something stupid. We had one guy on his way home from work who went to the store. His girlfriend picked him up at the store. That got him sent back. Little things like that.”

Sometimes they backslide in the difficult transition after release.

“It’s easy at the center,” Auger says. “They make them get up, get to work. When they get out, they have all this freedom, and they don’t know what to do.”

Superintendent Bass’ biggest issue is turnover. He and assistant Matt Chason oversee a maintenance staff that in season numbers a dozen or so, with eight to 10 staffers in winter. With one exception, the whole non-full-time staff is provided by the Second-Chance Program.

“The biggest challenge for me is, we only get them for like a maximum of nine, 10 months,” Bass says. “It’s constant turnover in both crews. I’d say 90% of them ... it’s very rare to find someone who has played golf or even been on a golf course. By the time you get ’em trained, they’re moving on.”

Patterson insists course conditions never suffer as a result. “And that’s a testament to the professional staff they have,” he says. “They’re real conscientious about training people the right way to do things. In all the years I’ve been out here, I’ve never seen one of those guys screw up. And in just the last couple of years, things have gone from it being a regular municipal course to just a really outstanding course. The new greenkeeper out there knows what he’s doing.”

Editor’s note: The training period lays the groundwork for how an employee performs and views their job. Check out Tips for better golf course staff training for strategies to instill attention to detail and inspire buy-in among greenhorn crew members.

The golfers at Hilaman and Jake Gaither have taken to their reentry crews.

“They love ’em,” Auger says. “The ladies are always asking if it’s time to start collecting winter clothes for the guys. They embrace them, treat them like family. We’ve not had hardly any issues at all. No golfer has ever said they don’t want to play here because we employ them.”

Auger likes to tell the story of Elijah Vickers, who came through the program in 2013 after eight years of incarceration.

While he was in prison, his wife went to live with her sister; his three boys moved in with a grandmother. As a result, Vickers became focused on buying a mobile home so they could reunite upon his release. Auger called around and was told if Vickers could pass the written portion of his CDL, he would qualify for a position in beautification, where he could join a program to help him pass the driving portion.

Vickers was concerned he wouldn’t be able to pass the written portion, but a member of the Hilaman Ladies Golf Association volunteered to help him prepare. They met at noon every Friday for six weeks. Vickers took the test ... and failed.

They studied more, and again he failed. Again they studied, and on the third try, he passed. He landed that OPS job in beautification and, that year, passed the driving portion of his CDL. He’s still a full-time employee for the city.

“By the way,” Auger adds, “he bought the trailer, and his family lives together.”

Dwaine Holloman

Current participants in the reentry program call Dwaine Holloman the GOAT — Greatest of All Time — and it’s not hard to see why. At the tail end of his 10-plus-year incarceration nearly a decade ago, Holloman enrolled in a fledgling Second-Chance Program, though another exception was required — too many prior convictions.

Holloman was one of the first to go through the program at the golf course. Today, he’s the course’s full-time mechanic.

“I didn’t really choose the golf course,” he says. “They chose me. But I like working outside better than working inside.”

Holloman, too, was wearing the dehumanizing prison-blue uniform the first time he stepped onto a golf course.

“Once I got out here,” he says, “I liked it.”

Holloman had worked as a mechanic before his incarceration, but many of the men following behind have no previous skills or even work experience.

“You have some come through who never had a job before,” he says. “Some really want to work. Those are the ones ... it’s a good program if you make use of it. Coming out of prison, they give you a chance. A lot of guys can’t find a job and end up right back in the system.”

Holloman is a man of few words, so Auger provides perhaps the most heartwarming part of his story. In part because Holloman made the most of his second chance, stayed out of prison and proved himself on the job, he and his wife were granted custody of their own grandchildren.

“Who knows what might have happened to those kids,” Auger says. “That’s something people tend not to think about.”

Andrew Hartsock is GCM’s managing editor.