Researchers in Nordic countries and the northern U.S. tested the limits of different grasses in cold environments and some clearly performed better than others. Photo by Pia Heltoft

Editor’s note: This article is reprinted with permission from the Feb. 21, 2025, issue of the USGA Green Section Record. Copyright USGA. All rights reserved. The original article can be accessed at: https://bit.ly/3XFj8XO.

Golf is played around the world, including many places with long, cold winters. In these locations, winter damage to putting greens is mainly a result of abiotic factors such as low temperatures, ice and freeze-thaw cycles — all of which are difficult or impossible to control. Diseases like Microdochium patch (Microdochium nivale) can also be problematic, particularly in Nordic countries where restrictions on the use of pesticides limit control options. In-depth knowledge about how different grasses perform in cold weather is crucial for reducing the risk of winter damage and its subsequent impacts on the playability and finances of a golf course.

In an effort to provide information that helps superintendents select the best grasses for areas prone to winter injury and diseases like Microdochium patch, a series of studies at two sites in the U.S. and in three Nordic countries was initiated by scientists with the SCANGREEN program. The results from their most recent round of testing can help golf course superintendents select grasses with the most consistent winter survivability and resistance to disease.

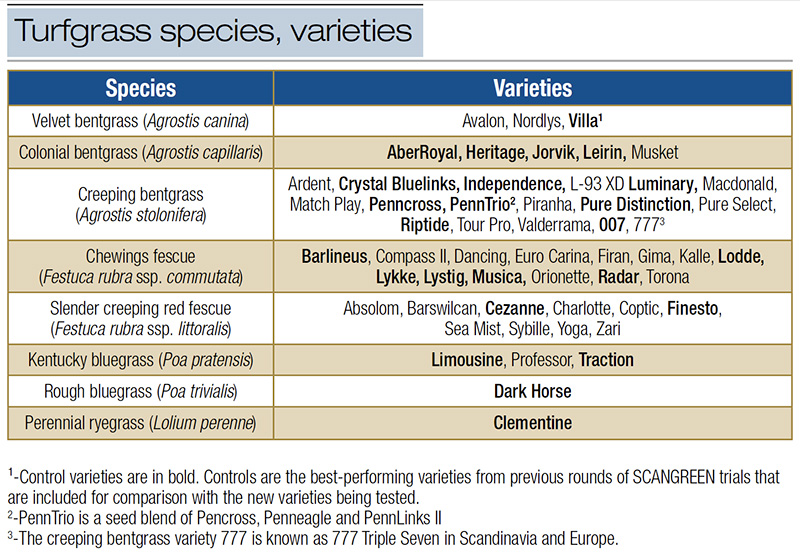

Table 1. Turfgrass species and varieties tested across four Nordic locations and two U.S. locations, Massachusetts and Minnesota.

Background on the SCANGREEN program

SCANGREEN (www.scanturf.org) is a research program that is funded by the Scandinavian Turfgrass Environmental Research Foundation (STERF, www.sterf.org). Its objective is to create discussions between plant breeders, seed companies and golf course superintendents to encourage awareness about new grass varieties and integrated pest management, as well as to support efforts in turfgrass breeding for cold environments. SCANGREEN is managed by the Norwegian Institute of Bioeconomy (NIBIO) and uses four Nordic test sites.

Since 2019, two U.S. trial sites, in Massachusetts and Minnesota, have been included in the program.

Putting greens in the Nordic countries are commonly seeded with creeping bentgrass or mixtures of colonial bentgrass and red fescue. The fescue is typically a mixture of the two subspecies, Chewings and slender creeping red fescue. Annual bluegrass is managed as a weed species on putting greens in Nordic countries, and it is rather abundant in northern areas as it will fill voids following winter damage. The use of velvet bentgrass is restricted to some golf courses in Finland, while rough bluegrass and perennial ryegrass are typically only used as nurse grasses to reestablish greens after winter damage in places with hard winter conditions. In extremely cold Nordic climates, severe winter damage often occurs, and it is common for courses to have to establish new grass in spring. To avoid too much Poa annua infestation (from the natural seed bank), some courses seed quickly, establishing rough bluegrass or perennial ryegrass in early spring just to have some green grass before bentgrass and fescue recover and start to grow again.

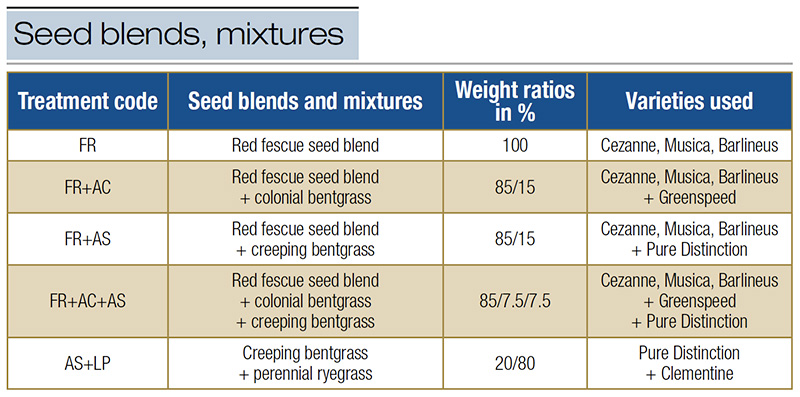

Table 2. The five seed blends and mixtures tested at the trial sites in Norway, Denmark and Minnesota.

2019-2022 SCANGREEN putting green trials

Grasses evaluated and locations

The SCANGREEN test round from 2019 to 2022 included eight different species and subspecies, with most entries being varieties of creeping bentgrass, Chewings fescue and slender creeping red fescue (Table 1).

The trials were established on putting greens built according to USGA recommendations at four Nordic locations: Reykjavik Golf Club, Iceland; NIBIO Apelsvoll and NIBIO Landvik research centers in Norway; and at Smørum Golf Club in Denmark. The annual mean temperatures at these four sites ranged from 40 to 49 degrees F (4.44 to 9.44 C), and the annual precipitation ranged from 26 to 56 inches (66 to 142 centimeters).

The two U.S. trials were established on a green built according to USGA recommendations located at Troll Turfgrass Research Facility at the University of Massachusetts, and on a native soil push-up green at the University of Minnesota. The average annual temperature and precipitation was 59 F (15 C) and 46 inches (117 centimeters) in Massachusetts and 47 F (8.3 C) and 32 inches (81 centimeters) in Minnesota, respectively.

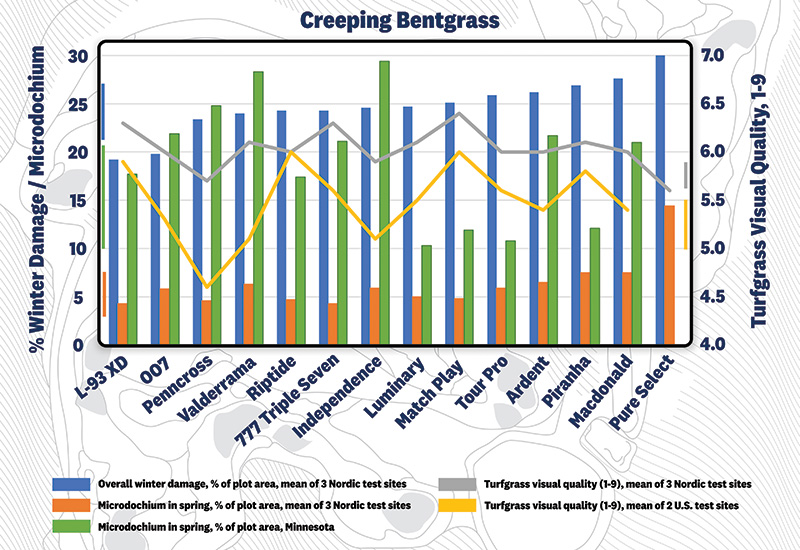

Figure 1. Results for 14 creeping bentgrass varieties evaluated for winter damage, Microdochium patch and turfgrass quality (entire growing season) in the SCANGREEN 2019-22 trials. Cultivars are ranked by increasing winter damage (blue bars) from left to right. The amount of disease in Minnesota (green bars) was significantly more than the average of three Nordic sites (orange bars) and may be due to differences in the species of Microdochium nivale present, climate and/or other factors.

Putting green establishment and management

The trials were established according to a split-plot design with three replicates; grass species were on main plots and varieties on subplots. The experimental greens were mown three times per week and deficit-irrigated to 80% of field capacity three to four times per week in periods without sufficient natural rainfall. Each experimental green was divided into two management levels (high or low mowing height and high or low nitrogen rate) based on the species’ potential use. All three bentgrasses (colonial, velvet and creeping) were mown at 0.120 inch (3.05 millimeters), with velvet and colonial bentgrass receiving 89 pounds of nitrogen per acre per year (99.76 kilograms per hectare per year), while creeping bentgrass received 152 pounds (170.37 kilograms) annually. At the 0.20-inch (5.08-millimeter) mowing height, red fescue received 89 pounds of nitrogen per acre per year, while perennial ryegrass, Kentucky bluegrass and rough bluegrass each received 152 pounds annually.

In addition to the species and cultivars listed above in Table 1, five seed blends containing various mixtures of three red fescue varieties, two bentgrass species and one perennial ryegrass variety were also tested and are listed in Table 2 in the results section. Those blends and mixtures were established from seed at the University of Minnesota, NIBIO Landvik research center in Norway and Smørum Golf Club in Denmark and were managed at both mowing and nitrogen regimes. There were some deviations from the maintenance protocol, especially during establishment and recovery after winter damage.

No notable differences were observed among nitrogen rate or mowing height treatments for the individual species and varieties listed in Table 1, and results are not discussed. However, another focus area of this research was to better understand how nitrogen fertilizer rate and mowing height impact which species in a seed blend becomes dominant. The results of testing five seed blends and mixtures of three red fescue varieties, two bentgrass species and one perennial ryegrass variety are discussed in the results section.

Treatment applications and data collection

Traffic was simulated across all plots and treatments using friction wear drums with golf spikes corresponding to an average of 11,000 rounds of golf per year. There was no use of pesticides or plant growth regulators in any of the trials. Further details on establishment and management can be found in the full report (3).

Monthly assessments of turfgrass quality, tiller density, color, leaf fineness and coverage of weeds and diseases were done from April or May to October or November depending on the site. Overall winter damage was recorded in spring and occurrence of diseases like Microdochium patch, gray snow mold (Typhula incarnata) and speckled snow mold (Typhula ishikariensis) were rated in autumn, early winter and spring.

Scientists evaluate winter diseases at the SCANGREEN site in Landvik, Norway, in April 2022. There were clear differences in susceptibility to winter turfgrass diseases among the varieties studied. Photo by Tatsiana Espevig

Results: Comparing different grass species and varieties

Across the Nordic countries, creeping bentgrass followed by velvet bentgrass gave the best overall quality. Both were significantly better than slender creeping red fescue, Kentucky bluegrass and Chewings fescue, which all performed equally. Perennial ryegrass and rough bluegrass had the lowest overall quality across all trial sites.

Varieties of Chewings, slender creeping red fescue

The varieties of Chewings fescue performed better than the varieties of slender creeping red fescue. The difference could be explained by more Microdochium patch during winter and more dollar spot (Clarireedia spp.) during summer in slender creeping red fescue. At Smørum Golf Club in Denmark, big differences between the varieties of slender creeping red fescue were observed with 20%-30% Microdochium patch during winter in several varieties compared to only 0.2% in Sea Mist and 3.0% in Cezanne. Sea Mist also had the lowest infection of dollar spot at Smørum, significantly lower than in several of the other varieties. Sea Mist also had the lowest infection of dollar spot in Massachusetts, although not significantly different from the other varieties. Overall, in the U.S., the variety Sea Mist performed the best of slender creeping red fescues across the two sites.

Varieties of colonial bentgrass

Across the four Nordic sites, there was no difference between the colonial bentgrass varieties in overall turfgrass quality, but Jorvik had the lowest overall winter damage and the least Microdochium patch across all years.

Varieties of creeping bentgrass

In total, 17 varieties of creeping bentgrass were tested (Figure 1). Across the Nordic test sites, Match Play, L-93 XD and 777 performed best, closely followed by Piranha, Valderrama and Luminary. Lowest ranked in the Nordic test zones were Penncross, which had significant disease, low tiller density and coarse leaves, and Pure Select, which had more overall winter damage and infection of Microdochium patch than the other varieties of creeping bentgrass. In contrast, Pure Select was ranked as third best in Massachusetts, but it was not tested in Minnesota.

The creeping bentgrass varieties tested at both trial sites in the U.S. show that Match Play, Riptide and L-93 XD were the three highest rated for overall turf quality, while Penncross, Independence and Valderrama were rated lowest. Luminary, TourPro, Match Play and Piranha had significantly less Microdochium patch than the other varieties, while Penncross, Independence and Valderrama had the most Microdochium patch across all observations. Dollar spot severity was also measured at the two U.S. sites, with Piranha having the least amount of in-season disease, while Independence had the most.

Varieties of velvet bentgrass and Kentucky bluegrass

Villa remained the top variety of velvet bentgrass for the Nordic countries in this round of testing, as it was in earlier trials. Villa also had slightly higher turfgrass quality than Legendary and Avalon in Minnesota, while Villa and Avalon were equal in Massachusetts.

In Kentucky bluegrass, Limousine produced higher turfgrass quality, higher tiller density, finer leaves and less in-season disease than the very dark-colored variety Professor. Compared to Professor, Limousine was also more winter hardy and less infested with moss and Poa annua. Mostly because of finer leaves, Traction was ranked higher than Limousine at Landvik and in Minnesota.

A spiked drum was used to simulate golf traffic on the plots. Photo by Karin J. Hesselsøe

Results: Comparing different seed blends and mixtures

Winter damage and disease performance

The first column in Table 2 lists the treatment codes for each of the five seed blends and mixtures tested. At the high-fertilizer/low-mow maintenance treatment, the mixture of fescue and creeping bentgrass (FR+AS) had the highest overall turfgrass quality in the Nordic trials, while the mixture of fescue and colonial bentgrass (FR+AC) was ranked the lowest. Comparing overall winter damage and Microdochium patch during winter, FR+AS was also significantly better than FR+AC. In contrast, the infection of Microdochium patch across years was higher with FR+AS than with FR+AC in Minnesota, but the three mixtures with fescue and bentgrass were nonetheless close in overall turfgrass quality in the U.S. trial. The mixture of creeping bentgrass and perennial ryegrass (AS+LP) was ranked the lowest in Minnesota with a high infection of Microdochium patch and coarse leaves.

How does mowing height and nitrogen rate affect species dominance in a blend?

The proportion of red fescue to bentgrass in the mixed plots was investigated by counting tillers in 2020 and 2021. The proportion between red fescue and bentgrass was in favor of the bentgrasses at high-fertilizer/low-mow maintenance. The highest proportion of bentgrass was found with FR+AS, followed by FR+AC+AS and FR+AC. At low-fertilizer/high-mow maintenance, the proportion between fescue and bentgrass was more balanced, though the FR+AC+AS mixture was in favor of the bentgrasses. In 2021, the dominance of creeping bentgrass was clear at high-fertilizer/low-mow maintenance, as red fescue was almost entirely outcompeted on plots seeded with the FR+AS mixture. In cases where red fescue is desired to be the dominant grass for aesthetic or traditional reasons, a higher mowing height and lower fertilizer rate will give it a competitive advantage over creeping and/or colonial bentgrass.

Implications for practitioners

Individual grass species and varieties

Among all grass species tested, creeping bentgrass was found to have the best overall quality under these specific conditions. The cultivars Match Play, L-93 XD and 777 are good options for the Nordic countries and northern parts of the U.S. Older cultivars like Penncross are not good options for locations where disease is a primary concern. Keep in mind that golf course superintendents in the U.S. have access to many fungicides that greenkeepers in Nordic countries do not. Therefore, superintendents in the U.S. may want to weigh factors such as turf quality and winter survivability more than disease resistance. Cultivars can also perform differently based on location, as illustrated with Pure Select, which did poorly in Norway but performed well in Massachusetts.

Although creeping bentgrass is commonly used in cold climates in the U.S., the results from this study and ongoing work show the potential for other grasses like velvet bentgrass and the fine fescues as options for golf courses in cold climates. In the right setting, Chewings fescue could be a good option for courses prone to Microdochium patch and dollar spot, specifically the variety Sea Mist. The findings regarding velvet bentgrass support previous research in the U.S. that shows when the right growing environment and golfer expectations are present, velvet bentgrass can provide a dense, fine and uniform putting surface that requires few inputs and tolerates diseases well (1, 2). The lack of velvet bentgrass seed and sod production currently limits widespread use of this grass in the U.S. The fine fescues and velvet bentgrass fit a very specific niche in the U.S. and require a unique maintenance program; nevertheless, they do offer benefits over other grasses when low inputs are desired.

Perennial ryegrass germinates quickly and can tolerate a wide range of mowing heights, but overall, it performed poorly at all sites except at Smørum. Rough bluegrass had the lowest turfgrass quality at all sites and is not a good grass choice for cold climates.

Seed blends and mixtures

Among the seed mixtures, a few clear differences were found. Fine fescue and creeping bentgrass blends would be preferred at Landvik, Smørum and similar climates in the U.S. at the high-nitrogen/low-mow maintenance, but with the risk that the creeping bentgrass outcompetes the fescue. Varieties of creeping bentgrass with a lower tiller density than Pure Distinction should be preferred for the mixture with fescue. Although the results of this research show that creeping bentgrass performs well in cold regions, golf courses in northern Europe sometimes desire to maintain it as a subordinate or supplemental grass to a red fescue blend for aesthetic, playability and, in some cases, traditional reasons. The mixture with creeping bentgrass and perennial ryegrass established significantly faster than any of the others, but following winter, turfgrass quality decreased significantly compared to the other mixtures due to Microdochium patch, so the blend with Clementine perennial ryegrass cannot be recommended for cold climates.

Reducing pesticide use

A key objective of the SCANGREEN program is to provide superintendents in Europe, who have limited pesticide options, with the best grass choices for use on courses that use little or no chemical inputs. For example, our results suggest that for courses with mixtures containing colonial bentgrass, replacing it with creeping bentgrass can reduce fungicide requirements. Again, golf course superintendents have many factors to weigh when it comes to grass choices, but if reducing fungicide inputs is a priority, selecting grass species and varieties with good disease tolerance is essential.

In this trial, the amount of Microdochium patch that occurred varied by bentgrass cultivar. The differences are apparent in this photo from April 2021 at the University of Minnesota. Photo by Andrew Hollman

Final thoughts

The information from this study can guide superintendents in selecting grasses that will perform well in cold climates, but as with any turfgrass conversion, testing potential grass options on a small scale in the unique environment and maintenance program of a particular golf course is essential for making the best choices.

The next round of trials by SCANGREEN has been funded by STERF for 2023-2026 and is currently underway. The U.S. trials are continuing in Minnesota and are now funded by the Winter Turf project (https://winterturf.umn.edu).

The research says

- Researchers tested grasses for winter survivability, overall quality and disease resistance in cold climates. Ability to resist diseases like Microdochium patch is particularly important in Europe where limited fungicide options exist, or for superintendents anywhere wishing to reduce fungicide use.

- Among eight grass species tested in Norway, Iceland, Denmark and the U.S., creeping bentgrass was ranked highest for overall quality. The top-performing cultivars were Match Play, L-93 XD and 777. There were significant differences in winter damage and disease among the 17 cultivars tested.

- Velvet bentgrass ranked second best in overall quality. Both creeping bentgrass and velvet bentgrass were significantly better than slender creeping red fescue, Kentucky bluegrass and Chewings fescue, which all performed equally. Rough bluegrass and perennial ryegrass were ranked lowest overall.

- Among five different seed mixtures tested, the creeping bentgrass variety Pure Distinction blended with three varieties of fine fescue performed best. Management strategy (nitrogen rate and mowing height) significantly impacts which grass becomes dominant in creeping bentgrass blends with other species.

Literature cited

- Boesch, B.P., and N.A. Mitkowski. 2007. Management of velvet bentgrass putting greens. Applied Turfgrass Science 4:1-6 (https://doi.org/10.1094/ATS-2007-0125-01-RS).

- Brilman, L.A. 2003. Velvet bentgrass (Agrostis canina L.). In: M.D. Casler and R.R. Duncan, eds. Turfgrass biology, genetics, and breeding. John Wiley & Sons, New York.

- Hesselsøe, K.J., A.F. Borchert, T.S. Aamlid, B. Hannesson, P. Rasmussen, K. Normann, T. Espevig, M. DaCosta, E. Watkins, A. Hollman, J. Hornslien, T. Petterson and P. Heltoft. 2023. SCANGREEN 2019-2022: Turfgrass species, varieties and seed mixtures for Scandinavian putting greens. Final results from a four-year testing period. NIBIO Rapport (https://hdl.handle.net/11250/3065144).

Trygve S. Aamlid is a research professor, Anne F. Borchert is a research scientist, Tatsiana Espevig is a research scientist and Karin J. Hesselsøe is a research scientist, all in the Division of Environment and Natural Resources at the Norwegian Institute of Bioeconomy, Landvik, Norway; Pia Heltoft is a research scientist in the Division of Food Production and Society at the Norwegian Institute of Bioeconomy, Apelsvoll, Norway; Michelle DaCosta is an associate professor in turfgrass science and management at the University of Massachusetts, Amherst; and Eric Watkins is a professor and Andrew Hollman is a researcher, both in the Department of Horticultural Sciences at the University of Minnesota, St. Paul.