Understanding how forced carries affect different players can help guide design and course setup decisions to create a reasonable challenge. Photos by Jaeger Kovich

Editor's note: This article is reprinted with permission from the Sept. 5, 2025, issue of the USGA Green Section Record. Copyright USGA. All rights reserved. The original article can be accessed here.

Overcoming challenges is part of what makes golf fun, and forced carries can be some of the most exciting — and daunting — shots in a round. Any golfer’s heart beats a little faster when they have no choice but to carry the difficulty in front of them — whether it’s a small pond, a swath of bunkers or a corner of the Pacific Ocean. Confronting these challenges can add to the enjoyment of playing, but we must also recognize that forced carries affect golfers differently depending on skill level. If a carry is excessive for too many players, it can lead to frustration and a slower pace of play.

To better understand how forced carries impact different players, the USGA conducted a quantitative analysis of golfer performance in three different forced-carry scenarios at an individual golf course. We built on those results with another study involving the most extreme example of a forced-carry scenario — an island green par 3. We collected data on how different types of golfers approached these challenges and what their success rates were. It’s not surprising that shorter hitters and less-skilled players have more difficulty with forced carries, but identifying the various thresholds that impact behavior and outcomes is valuable information for golf course architects, superintendents and golf professionals as they try to create an appropriate challenge for different golfers.

The par-5 12th hole on the right of this image and the par-3 13th on the left were two of the three forced-carry holes studied at Cedarbrook Country Club in Blue Bell, Pa.

Study 1: Three forced-carry

Scenarios at one golf course

During the fall of 2021, the USGA conducted a research study at Cedarbrook Country Club in Blue Bell, Pa., on holes with forced carries in front of the green. USGA staff measured golfers’ distance from the flagstick as the forced carry came into play, observed whether each golfer laid up or attempted to carry the penalty area and recorded the result of each shot. Over the course of three weeks, 1,350 shots were observed across three different holes with forced carries on the shot into the green (one par 3, one par 4 and one par 5). Eighty-eight percent of the shots were by male golfers and 12% by female golfers.

Sample of golfers

Each golfer’s apparent gender was recorded. While we did not have access to their Handicap Index, we were able to observe play during situations that broadly included golfers of distinct skill levels. First, we observed play during The Hogan, which is a one-day event for highly skilled male golfers. Most of the golfers in the event had a near scratch or better Handicap Index. We also collected data during three Monday outings and during regular play by members and their guests. Members and guests would typically be expected to have a higher average skill level than players in the outings, but not as skilled as the players in The Hogan event.

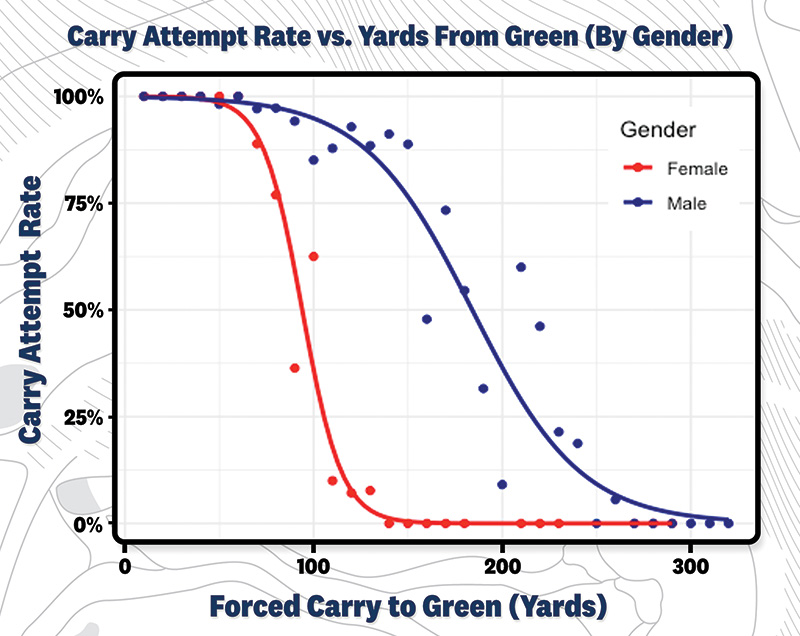

Figure 1. At 125 yards away from the green, only 5% of female golfers in this study attempted the carry compared to about 88% of male golfers.

Methodology

As each golfer played the holes of interest, USGA staff recorded their distance from the flagstick as they came into range of the forced carry to the green. Because the flagstick was used as the reference point and typically changes daily, adjustments were made using hole location sheets to determine the distance from each shot to the center of the green. These adjustments make day-to-day measurements directly comparable.

We also recorded the golfers’ gender and judged whether they were attempting to make the forced carry or to lay up. The outcome of each shot was recorded as a success or a failure after the attempt. Shots were considered a success if the golfer accomplished their objective related to the forced carry. For example, if the golfer attempts a carry and the shot lands in the penalty area, it was recorded as a failure. Alternatively, if the golfer attempts to lay up and the ball ends up short of the penalty area, it is recorded as a success.

Attempted forced carry frequency by distance

This section breaks down how frequently different types of golfers attempted to make the forced carries from varying distances.

By gender

There was a clear difference in how male and female golfers handled the forced-carry situations. In Figure 1, it can be seen that female golfers generally lay up at shorter distances than males. For example, at 125 yards away from the green, only 5% of females will attempt the carry compared to about 88% of males.

We can also see where forced carry distance starts to impact golfer strategy. Female golfer decision-making is affected starting about 50-60 yards from the hole. By 90-95 yards, nearly half of female golfers are laying up, and by 150 yards, virtually all female golfers lay up. Male golfer decision-making begins to be impacted at 60-70 yards from the hole. By about 180 yards, nearly half of male golfers are laying up, and it is not until over 250 yards that virtually all male golfers lay up.

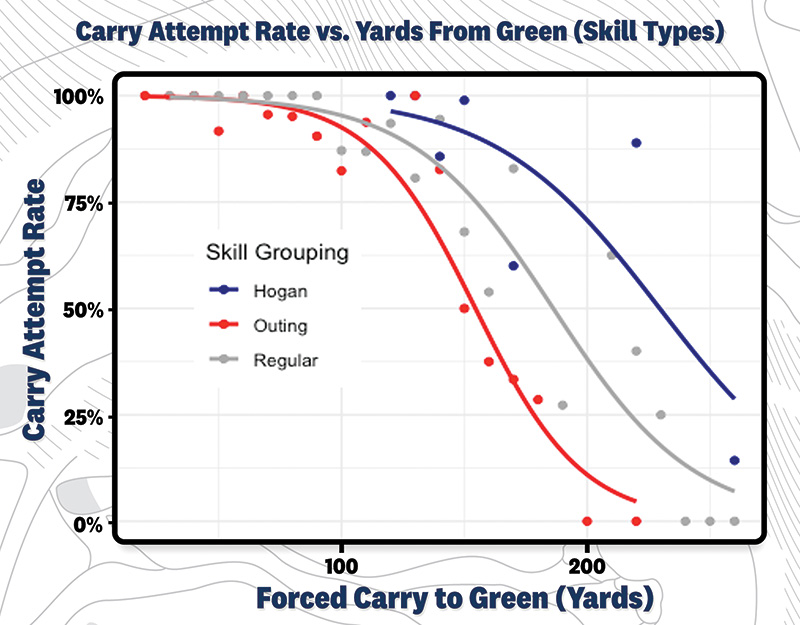

Figure 2. Golfers playing in an outing (“Outing”) were much less likely to attempt a forced carry of 150 yards than highly skilled golfers playing in a tournament (“Hogan”).

By skill

Trends in forced-carry behavior are also a function of skill. In Figure 2, “Hogan” refers to the highest-skilled group of male players in this study, “Regular” refers to normal member and guest play with a range of skill levels, and “Outing” golfers were all male players who participated in one of three Monday outings. Regular golfers accounted for 56% of observed shots (752 shots), Hogan golfers 13% (176 shots) and Outing golfers 31% (424 shots). The study showed that lower-skilled male golfers generally lay up at shorter distances than highly skilled male golfers, which would be expected. For instance, at 150 yards from the green, 55% of Outing golfers attempted the forced carry, 77% of Regular members and guests attempted to carry and over 90% of the highly skilled Hogan golfers attempted to carry.

Success rates on forced carries by distance

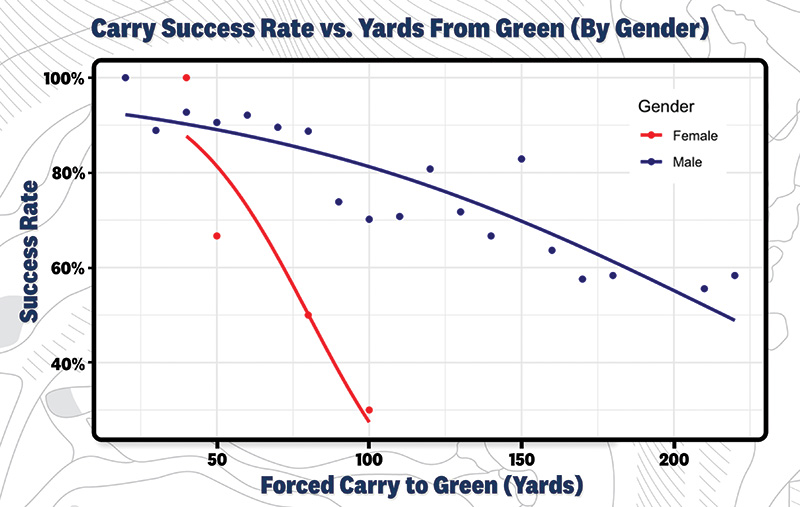

By gender

Figure 3 demonstrates gender differences in success rate on forced carries. There is a sharper decline in success rate for female golfers compared to males as distance from the green increases. At 75 yards, females have a 55% success rate on carries compared to an 85% success rate for males. By 100 yards, female success rate drops to 30% versus males being over 80%, which reinforces the disproportionate effect of forced carries on shorter-hitting golfers.

Figure 3. This data shows a much sharper decline in forced carry success rate among female golfers than male golfers as the carry distance gets longer. Of the 1,350 shots observed, 162 were by female golfers and 1,188 shots were by male golfers.

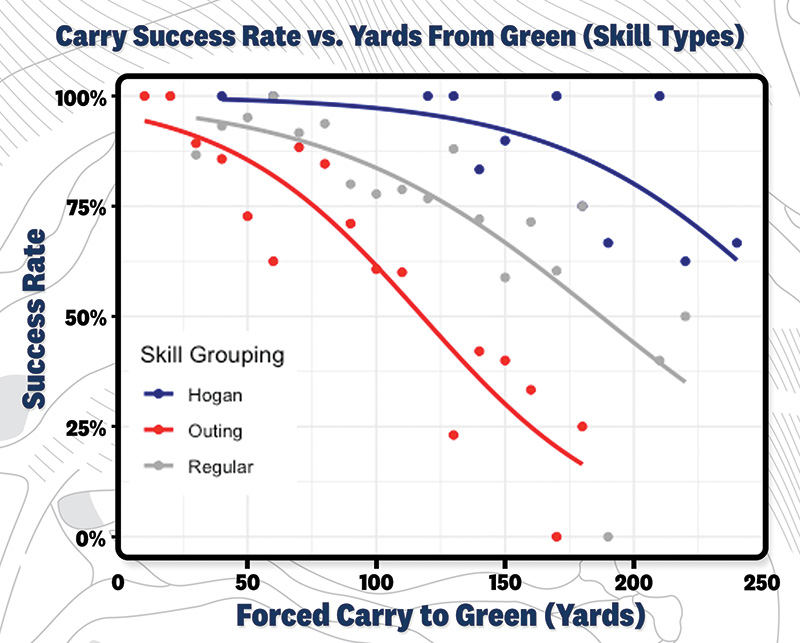

By skill

Similar trends can be seen when breaking down the results based on the skill level of male golfers. Figure 4 shows that the highest-skilled male golfers have higher success rates on carries compared to lower-skilled golfers. At 150 yards away from the center of the green, 90% of high-skilled golfers succeed on the carry compared to 70% success for male member and guest play and 31% success for male golfers from outings.

Conclusions from Study 1

These results highlight the differences in how players with various hitting distances and skill levels are affected by forced carries. Once the distance to the center of the green over a forced carry reaches 100-125 yards, the vast majority of female golfers in this study would either lay up short of the penalty area or would be unsuccessful in attempting the carry. Male golfers playing in outings during this study attempted the carry 55% of the time at 150 yards and were successful 31% of the time from that distance. Contrasting these results with those from highly skilled male players who participated in a one-day tournament illustrates the challenge of designing and setting up a golf course for a wide range of players.

Figure 4. The decline in success rate with increased forced carry distance occurs more rapidly among less-skilled golfers and begins at shorter distances. Only 31% of golfers playing in outings were successful when attempting a 150-yard forced carry.

Based on the results, a forced carry of more than 100 yards should be avoided if female golfers and others with slower swing speeds will be affected. At 75 yards, 45% of female golfers attempting forced carries were still unsuccessful. For male golfers, the success rate for a 150-yard shot to a green over a forced carry ranged from 90% for highly skilled players to 70% for member and guest play to 30% for outing play. The performance variation at different distances points to thresholds that can be useful for architects as they design holes with forced carries and for those tasked with course setup for daily play and events. For example, if an outing is likely to be composed of less-skilled players who are not familiar with the course, it may be wise to move the tees on holes with forced carries farther forward for that event to give players the best chance possible and to expedite pace of play by minimizing the number of layup shots and failed attempts at the carry.

When it comes to challenging highly skilled male golfers with forced carries, approximately 75% of those players attempted a forced carry of 200 yards, and they were successful more than 75% of the time at that distance. From 150 yards, this group of players successfully made the carry 90% of the time. This points to a threshold at or above 200 yards for a forced-carry approach to have a significant impact on the strategy and scoring of highly skilled male golfers.

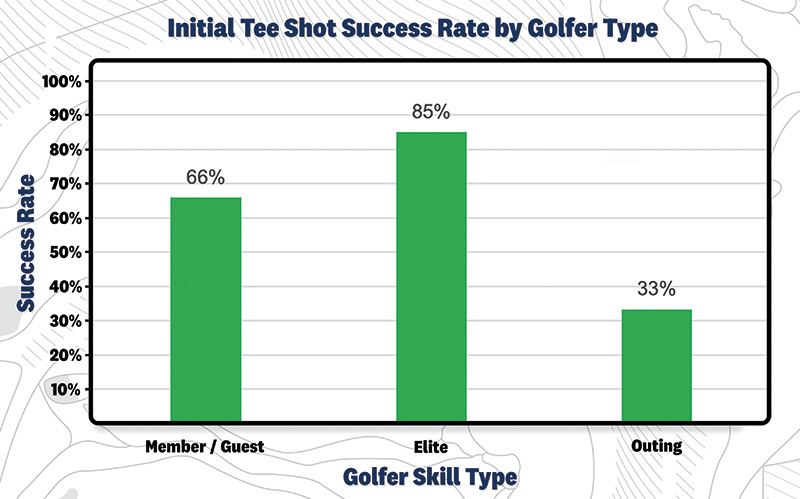

Figure 5. As observed in the previous study, golfers playing in outings struggled to successfully navigate the forced carry more than other types of players.

Study 2: Par-3 island green

To build on the results of the initial forced carry study, a second study focused on an extreme example of a forced-carry scenario — an island green par 3. Over the course of a full golf season in 2024, a researcher recorded the shot results of 841 golfers playing the island green par-3 15th hole at Savannah Quarters Country Club in Pooler, Ga. Tee shot distance on this hole to the middle of the green ranges from 96 yards from the shortest tee to 138 yards from the back tee. The green is larger than average, measuring about 46 yards long by 25 yards wide with roughly 9,000-10,000 square feet of area. The band of short grass and rough surrounding the green is about 3-5 yards wide from the edge of the green to the water, adding additional area for shots to land safely.

Methodology

Observations were made near the 15th tee without engaging with the golfers. Each golfer’s apparent gender was recorded. While we did not have access to the golfers’ Handicap Index, we were able to estimate their general skill level. Proximity to the tee also allowed the type of club to be discerned (iron, hybrid/wood or driver). The tee played (out of six tee options), the hole location and the shot result were also recorded. If the first tee shot failed, the number of retry attempts was recorded, along with any change in club selection and whether the golfer was ultimately successful in getting a shot to stay on the green.

Sample of golfers

A total of 841 golfers were observed playing the hole from Feb. 15 to Dec. 7, 2024. This group was 81% male and 19% female. Nearly 95% of female golfers played one of the two shortest tees, with only about 5% playing one of the longer four tees available. Only one male golfer played the shortest tee, 33% played the second shortest tee, another 29% played the third longest tee, and the rest of the golfers (37%) were distributed across the longest three tees in decreasing frequency as the shot got longer. Ninety-nine percent of male golfers used an iron for their initial tee shot, regardless of which tee was played. Even though 95% of female golfers played one of the two shortest tees, nearly one-third used a hybrid, wood or driver for their initial tee shot. The majority of the golfers were either members or their guests. We also observed a few elite golfers in the group who were identifiable by their swing and ball-striking ability.

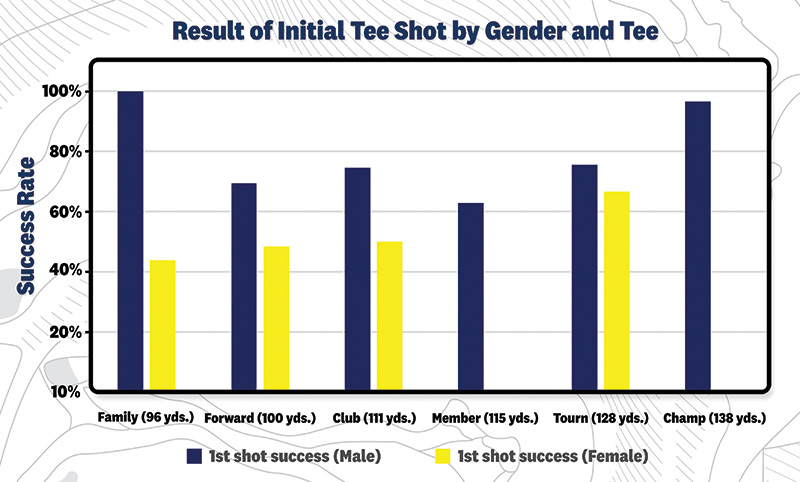

Figure 6. Success rates on the tee shot varied by gender and tee. Male golfers had higher success than female golfers across all tees, with the gap narrowing on the tournament tees, likely due to higher-skilled players using those tees. Additionally, no female golfers played from either the "Member" or "Champ" tees.

Results of initial tee shot

For this study, success is defined as hitting a tee shot that ends up anywhere on the island, including rough and collar areas. Golfers were categorized as Members/Guests (83% of sample), Elite (15% of sample) or Outing (2% of sample), and the success rate for their initial shot varied significantly. Golfers classified as elite had an 85% success rate, while members and guests were successful 66% of the time (Figure 5). Outing guests struggled, with only a 33% success rate.

The success and failure rates of the initial tee shot varied significantly by gender (Figure 6). The initial tee shot of male golfers was successful 73% of the time, compared to 47% for female golfers. The success rate by gender was further broken down by tee played. For every tee played, male success rates are higher than female success rates. Success rates between male and female golfers are closest on the tournament tees, presumably because highly skilled male and female players would be the ones generally selecting long tee shots on this hole, and they would have comparably high rates of success. The success rate of female golfers is lowest for those playing the shortest tees and improves on the tees farther back. This shows that the forced carry is hardest for the shortest-hitting or least-skilled female golfers who don’t have an option to move any farther forward.

In this study, the green was divided laterally into three zones: left, middle and right. These zones were about 8 yards wide. The green was also divided longitudinally into three zones: front, middle and back. Each of these zones was about 15 yards in length. Combining the lateral and longitudinal sections yields nine zones across the green. Failure rate varied significantly from zone to zone as shown in Figure 7). The most dangerous zone was the front/right zone, with a 57% failure rate. The lowest failure rates (20%-25%) occurred when hole locations were middle/middle, back/middle and back/left.

Figure 7. This graphic depicts the island green from the study, with percentages representing the success rate of the initial tee shot when the flag was located in each area. Golfers had a higher success rate when the flag was placed farther back on the green. Note: This graphic represents the actual green, which was divided into nine equal sections approximately 8 yards wide and 15 yards long.

Conclusions from Study 2

Success rates in this study correlated closely with what would have been expected based on the data from Study 1. Overall, 68% of 841 first tee shots were successful. Male golfers had a 73% success rate, while female golfers had a 47% success rate, showing that as in the previous study, forced carries are disproportionally challenging for female and shorter-hitting golfers. Female golfers playing the most-forward tee had the lowest success rate of the female players, showing that they simply did not have an option close enough to obtain a better result. Data from this study also pointed to the potential impact of hole location on success rate. With most failures winding up short of the green in this study (greater than 70% for females and 50% for males), it is likely that hole locations farther back encouraged players to hit longer shots that led to a higher success rate. The tendency of golfers to miss short more often than long on any type of approach shot is commonly observed and has even more impact in a forced carry situation. To increase the success rate of a forced carry on a particular day – e.g., during an outing — setup staff may want to place hole locations on greens with forced carries farther back to increase the chance of player success and improve pace of play.

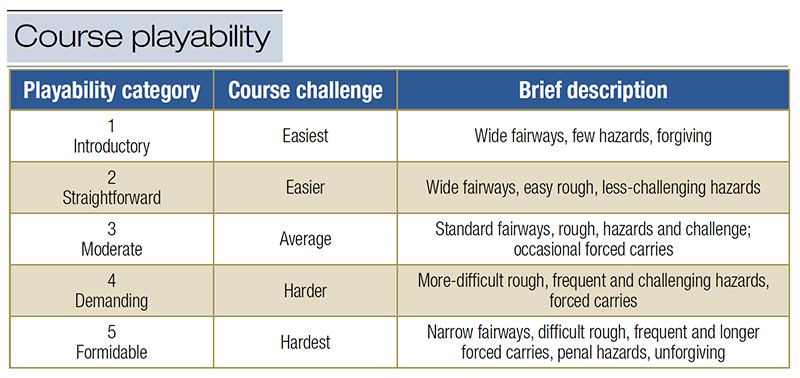

Table 1. This table shows a proposed course classification system based on challenge that the USGA tested at golf facilities around the U.S.

Helping players account for course difficulty

Two key takeaways from these forced-carry studies are that shorter hitters and players in outings have the greatest difficulty when it comes to handling forced carries. Length of carry also has a big impact on rate of success, so trying to help golfers reach a manageable point from which to attempt a forced carry is advantageous from the standpoint of providing a reasonable challenge and facilitating better pace of play.

The USGA is actively testing a system to help golfers select a tee that matches their skill level and hitting distance based on how far they hit their 7-iron. For courses that have adopted this system and golfers who choose to use it, it’s a substantial step forward in having more fun and playing the course as the designer intended. However, there is more to making a good tee selection than scorecard yardage alone. Some courses play longer or more difficult than others at the same total distance. The presence of forced carries can be a key factor that makes a course more difficult than others with a similar yardage.

How do you adjust tee selection to account for such challenges? How do golfers know they should make an adjustment if they haven’t played the course before? The World Handicap System expresses this information in the Course Rating and Slope Rating numbers that golf courses are assigned, but few golfers understand what these metrics actually mean, and there is currently no direct way to translate this information into a tee selection recommendation.

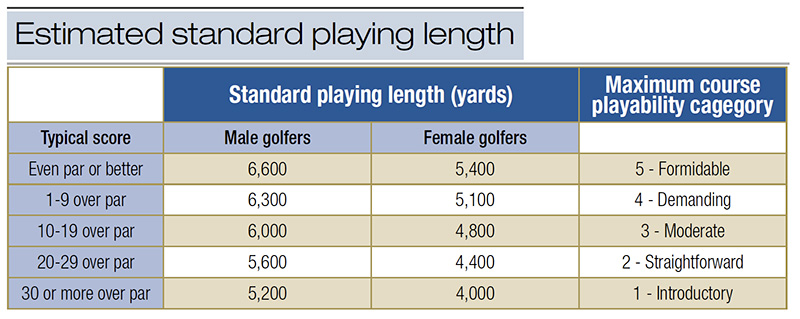

Table 2. This table shows estimated standard playing lengths for golfers of different skill levels and genders on courses of varying playability. Using these estimates as a baseline makes it easier for golfers to adjust tee selection when playing a course that is easier or more difficult.

Course playability and obstacles

Accounting for difficulties like forced carries is an important part of choosing a set of tees that is a good fit for a golfer’s game. For example, the overall scorecard yardage might be reasonable for your skill level, but there could be several holes that feature forced carries that are too difficult from that set of tees. There are metrics within the Course Rating System that can help categorize courses by playability. During course rating, obstacles that the golfers face are evaluated based on the likelihood that an obstacle will come into play and the difficulty in recovering from the obstacle.

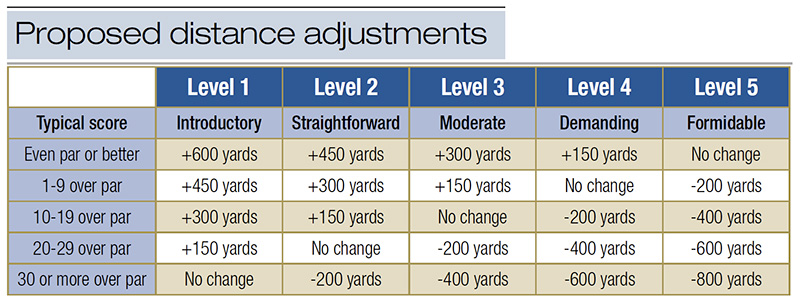

Using the available data, a method has been proposed and is being tested to put courses into five categories of course playability as shown in Table 1.

Most golfers can identify a course and tee that provides an enjoyable experience as a reference point. This would create the basis for their Standard Playing Length and Playability Category shown in Table 2. They can also use their typical score over par on an 18-hole course as a reference.

For example, a female golfer who scores 98 on average, or 26 over par on a par-72, 18-hole course would have a standard playing length of 4,400 yards on a Level 2 golf course (Straightforward/Easier). If that same golfer chose to play a Level 4 or “Demanding” course, they could use Table 3 to adjust their recommended playing length for an equivalent experience. For this golfer, the chart shows minus-400 yards, so this golfer’s ideal playing length on a demanding course would be 4,000 yards, and they would select the tee closest to this yardage.

As another example, suppose a highly skilled male golfer knows his preferred playing length is 6,425 yards on a Level 5 or “Formidable” course. On a certain day, he is playing a “Moderate” or Level 3 course, so his recommended playing length for that course would be plus-300 yards, or 6,725 yards for an equivalent experience. The distance adjustments in this chart have been proposed based on experience from previous studies and are continuing to be refined.

Table 3. Golfer tee selection should account for course difficulty as well as total yardage. On a more-difficult course, golfers may want to play from a shorter distance than normal to experience a comparable challenge.

How a golf facility can utilize this information

Whether it’s new customers at a daily fee or resort course, guests of a member at a private facility or people playing a course for the first time in an outing, there are many scenarios where golfers don’t know what they’re in for when they play a course. There are also many examples of players who know a course well but routinely choose a tee that is too far back for their playing ability because they are basing the decision on scorecard yardage rather than the unique challenges of that course.

This system can help golf courses communicate with golfers about course playability and help them choose a set of tees that fits their hitting distance and skill level given the challenges of that course. Simple signage can be posted to identify the playability level to golfers prior to teeing off. Staff in the golf shop or at the first tee can also be trained to engage with golfers to discuss their skill level and normal playing distances and how to adjust for the best possible playing experience at that course.

The research says

- Forced carries are more difficult for shorter hitters, less-skilled golfers and golfers playing in outings.

- Forced carries of more than 100 yards were too difficult for the majority of female players in this study.

- Golfers playing in outings had a much lower success rate on forced carries than members or their guests at the two courses studied. Outing setup should take this into account if forced carries are present.

- The length of a forced carry and the hole location have an influence on success rate.

- The USGA has developed a tee selection guide that accounts for challenges like forced carries and helps golfers adjust their chosen playing length to match the difficulty of a particular course.

David Pierce, M.S., M.B.A., is president of Stellar Golf Advisors and past director of USGA Green Section Research.