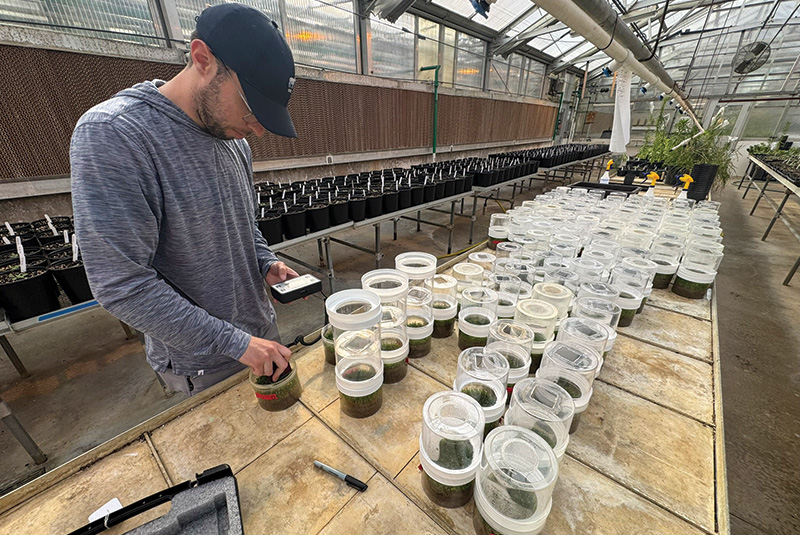

Photo courtesy of Ben McGraw

Effects of moisture management on annual bluegrass weevil oviposition and larval survival

The annual bluegrass weevil (ABW) is one of the most destructive insect pests of cool-season turf, causing severe damage to Poa annua and, to a lesser extent, Agrostis stolonifera. Populations are typically most dense and damaging in spring, when precipitation is abundant, soil moisture is high, and their preferred host thrives. Summer generations have been anecdotally reported to persist only in well-irrigated or low-lying areas, suggesting that soil and plant moisture may influence ABW behavior, development and survival. In choice assays, females showed no significant oviposition preference among low (10%-15% VWC), medium (20%-25%) and high (30%-35%) soil moisture treatments. Slight tendencies toward wetter soils were observed, though all females tested were unmated, limiting inference about egg-laying behavior. No-choice trials revealed that soil moisture influenced early larval survival, although the trend was not consistent between experiments.

These contrasting outcomes suggest that the duration of soil moisture stress may differentially affect egg survival and early larval development. A third objective evaluated larval survivorship through a life table approach. Although larval abundance declined across all treatments with time, only the low-moisture treatment exhibited a significant reduction in larval numbers from 14 to 24 days post-infestation, suggesting that prolonged dryness may negatively affect survivorship. Collectively, these preliminary findings indicate that soil moisture may exert subtle but biologically relevant effects on ABW development. Ongoing work in 2026 will replicate these experiments and extend the research to field trials examining how precipitation and irrigation regimes influence larvicide efficacy and ABW management under changing climatic conditions.

— Zachary T. Newsome (ztn5010@psu.edu) and Ben McGraw, Ph.D., Pennsylvania State University, University Park

Photo by Darrell J. Pehr

Exploring interactions between root-knot nematodes and take-all root rot on hybrid bermudagrass quality and disease severity

High populations of plant-parasitic nematodes, especially the root-knot nematode (Meloidogyne spp.), have been frequently associated with turfgrass samples expressing symptoms and signs of take-all root rot, a crown and root disease caused by a complex of ectotrophic root-infecting fungi. The two soil-borne pathogens express similar symptomology, and the ecology between the two is largely unknown. The present study analyzes the relationship between take-all root rot and root-knot nematode infection on hybrid bermudagrass for its impact on disease severity and turfgrass quality. Pots of hybrid bermudagrass [Cynodon dactylon (L.) Pers. × C. transvaalensis (Burtt-Davy) cv. Miniverde] were grown in the greenhouse and exposed to one of four treatments: non-inoculated control (C), nematode only (N), fungus only (F) and nematode plus fungus inoculation (NF). Approximately 600 second-stage juvenile (J2) root-knot nematodes (M. graminis) were inoculated on treatments N and NF. Then, 10 weeks after nematode inoculation, two 0.2-inch (5-millimeter) potato dextrose agar plugs with fresh Guaemannomyces graminis var. graminis (GGG) growth were inoculated on treatments F and NF. Visual turf quality and percent green cover were evaluated weekly throughout the duration of the study using digital image analysis.

At the end of the experiment, basal necrosis, root area and nematode populations were evaluated. Pots inoculated with M. graminis and/or GGG declined in visual turf quality and percent green over a period compared to the control treatment, and there was no significant difference between the N and F treatments in all turf quality parameters. Furthermore, turf quality and percent green cover declined more rapidly and to a greater extent when both pathogens were inoculated compared to single pathogen treatments. The results of this study suggest that when turfgrass is under pressure from more than one pathogen, overall quality and vigor may decline more rapidly than turfgrass facing a single pathogen.

— Jason Todd (jltodd@clemson.edu) and Joseph Roberts, Ph.D., Clemson University, Clemson, S.C.