Ice encases turf at the Hancock Turfgrass Research Center at Michigan State University in East Lansing. Photos by Devendra Prasad Chalise

Annual bluegrass (Poa annua) putting greens often face major winter weather challenges like ice encasement. When thick, nonporous ice covers the turfgrass surface for several weeks, it can create low oxygen conditions (hypoxia), which can harm the grass and cause winterkill. Prolonged hypoxic conditions during winter can result in plant overwintering tissues switching from normal metabolism (respiration) to an alternate, backup energy metabolism (anaerobic respiration). Researchers at Michigan State University conducted a study to document direct evidence of this switch to anaerobic metabolism by measuring byproducts of this metabolism and the activity of enzymes involved in anaerobic metabolism in annual bluegrass leaf, crown and root tissues after 0, 40 or 60 days of ice encasement.

Understanding if and when anaerobic metabolism is occurring in annual bluegrass assists in generating recommendations for well-timed management strategies. The study indicates the necessity to prevent prolonged ice encasement from causing low oxygen conditions.

Why is low oxygen damaging to turf?

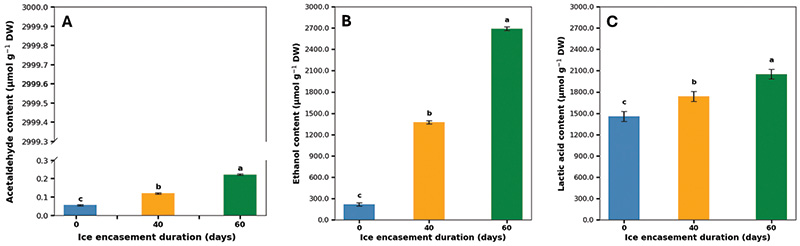

Low oxygen levels in a turf and soil system, such as due to standing water, saturated soils or ice encasement, cause anaerobic metabolism. Anaerobic metabolism produces byproducts that are harmful to grass cells. This type of metabolism is an inefficient way to produce energy from carbohydrates compared to normal metabolic processes like respiration. Those byproducts, such as ethanol, acetaldehyde and lactic acid, are the same as those causing discomfort in human bodies after intense exercise (muscle soreness) or consumption of alcohol (hangover effects).

After 60 days of ice encasement, ethanol levels in the grass were 12 times higher than in grass that was not encased (Figure 1). High ethanol levels can damage cells. The study also found that certain enzymes involved in anaerobic metabolism, like alcohol dehydrogenase, were highly active after ice encasement. However, another enzyme, pyruvate decarboxylase, which is crucial for tolerating low oxygen conditions in other plant species, did not increase as much, especially in the roots. This insufficiency may make annual bluegrass less able to survive under ice compared to other grass species like creeping bentgrass. A major takeaway from this study is the high level of damaging ethanol and lactic acid we found after just 40 days (or close to six weeks) of ice encasement (Figure 1). This makes us suppose that it is likely even after just a week or two of ice encasement that annual bluegrass may be switching to anaerobic metabolism, and these byproducts are being generated and could trigger turf stress and/or damage.

Figure 1. Anaerobic metabolites in annual bluegrass: (A) acetaldehyde, (B) ethanol and (C) lactic acid content across ice encasement durations (0, 40, 60 days).

Another challenge: Oxidative stress in low oxygen conditions

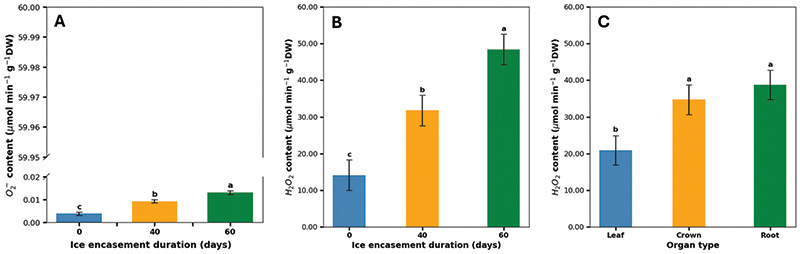

While counterintuitive, cellular stress resulting from low oxygen conditions can also produce oxidative stress, or the presence of reactive oxygen species (ROS), in plant tissues. These are harmful molecules that damage cellular components. An example of an ROS is hydrogen peroxide (H2O2). We all know the sting of hydrogen peroxide when it is poured onto a wound. This study investigated oxidative stress and antioxidant responses in annual bluegrass structures and showed that this type of sting is felt in annual bluegrass’s cells overwinter and coming out of winter in the spring, unfortunately in all tissue structures evaluated: leaves, roots and crowns.

The longer the grass was encased in ice, the more ROS that were produced (Figure 2). For example, after 60 days, hydrogen peroxide levels were more than three times higher than in grass that was not encased in ice. The roots and crown had higher levels of these harmful molecules compared to the leaves, making them more vulnerable to damage or more likely to succumb to winterkill. There was limited antioxidant enzyme activity in crown and root tissues, meaning annual bluegrass may not have a strong antioxidant system for stress defense in these structures, particularly with a weakened metabolism due to low oxygen conditions.

Figure 2. Reactive oxygen species in annual bluegrass: (A) superoxide anion (O2-), (B–C) hydrogen peroxide (H2O2) across ice encasement durations and plant organs.

How should turf be managed after ice encasement?

The results of the study reinforce recommendations for turfgrass managers in northern regions to closely monitor all putting greens for ice encasement presence. All winters are not created equal, so ice encasement monitoring may be more important in some years compared to others, but since ice is so damaging, it should still be monitored for each year. Each green should be monitored and considered independently. Soil, thatch and microclimate differences will mean that not all putting greens may experience ice encasement. Those putting greens that have a high percentage of annual bluegrass, a history of ice, those that may be more shaded, or have poor drainage should be monitored closely for ice encasement presence. A calendar could be kept for each putting green to document length of ice presence.

Those putting greens that experienced even just a few weeks of ice encasement should be acknowledged, noted and treated accordingly. Recovery strategies should be implemented in spring, and yearlong management strategy adjustments should be made to improve turf and soil health so that future recurrences of ice encasement may be reduced on a given putting green.

During and after even relatively short periods of ice encasement like 40 days or possibly less, annual bluegrass not only may feel like it has a hangover but is stressed out, and defense systems are tired. During winter and spring, treat turf exposed to ice encasement as you would want to be treated in a stressed-out state: gently. Refrain from traffic on putting greens in winter or very early spring if the putting green has had some ice encasement. Mowing early is tempting, but is it really needed on all greens? For ice-affected greens, even a week delay for certain cultural practices like mowing and fertilization with heavy spray equipment could help annual bluegrass recover. If resources allow, try to do the major, heavy cultural practices in the fall. However, additional research on spring management practices after different ice encasement exposures is needed.

Fall management practices that allow putting greens to start out with high levels of oxygen may be the best way to prevent or delay the onset of hypoxia and anaerobic metabolism. Cutting back on fall irrigation, thatch management, aerification with sand top-dressing, improving drainage and creating sod cut gutters to redirect rain, snow and ice melt water will help prevent and prolong the time required for anaerobic conditions to form on putting greens. Covering greens is also a primary way to keep putting greens dry and prevent ice encasement exposure. Putting greens that start out with high levels of oxygen will likely take longer to develop damaging anaerobic conditions and give annual bluegrass a better chance of winter survival.

Significant snowfall covers the terrain at the Hancock Turfgrass Research Center during the winter of 2024-2025.

The research says

- It is likely even after just a week or two of ice encasement that annual bluegrass may be switching to anaerobic metabolism and harmful byproducts are being generated and could trigger turf stress and/or damage.

- All winters are not created equal so ice encasement monitoring may be more important in some years compared to others, but since ice is so damaging it should still be monitored for each year.

- Those putting greens that have a high percentage of annual bluegrass, a history of ice, those that may be more shaded, or have poor drainage should be monitored closely for ice encasement presence.

- During winter and spring, treat turf exposed to ice encasement as you would want to be treated in a stressed-out state: gently. Refrain from traffic on putting greens in winter or very early spring if the putting green has had some ice encasement.

- For ice-affected greens, even a week delay for certain cultural practices like mowing and fertilization with heavy spray equipment could help annual bluegrass recover. If resources allow, try to do the major, heavy cultural practices in the fall.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the U.S. Department of Agriculture, National Institute of Food and Agriculture, Specialty Crop Research Initiative, under award number 2021-51181-35861 and the Michigan Turfgrass Foundation for funding and supporting this research. The results and figures in this article were adapted from an article previously published by the authors: Anaerobic and Antioxidant Activity in Annual Bluegrass (Poa annua) Following Ice Encasement Stress. Journal of Agronomy and Crop Science 211:e70101 (https://doi.org/10.1111/jac.70101).

Devendra Prasad Chalise (chalised@msu.edu) is a graduate student, and Emily Merewitz, Ph.D., is an associate professor and plant physiologist, both in the Department of Plant, Soil, and Microbial Sciences, Michigan State University, East Lansing.