Clearly defining expectations and holding employees accountable are among the hallmarks of effective management. Here, Kyle Marshall (left), superintendent at Rancho San Joaquin Golf Course in Irvine, Calif., gives instruction to crew member Julian Cornejo. Photo courtesy of Dave Waymire

Throughout my 16 years as a regional agronomist, working with multiple golf course superintendents and their maintenance crews, I’ve found that many superintendents — and general managers, for that matter — struggle with basic performance-management skills. Addressing substandard performance, holding people accountable and rewarding good work are aspects of a superintendent’s job that can seem rudimentary, but they’re often quite difficult. Many of you have likely attended seminars and read books or articles on this topic, so you’re already aware of what’s involved in the day-to-day leadership of a team. In my experience, however, knowing such principles and implementing them are two very different things.

With the golf business facing challenges on the revenue side and courses fighting to hold expenses in line, getting the most out of your crew is essential. Although natural leadership skills are extremely beneficial, the good news is that performance management can be learned. You needn’t be born with it, but you do need to understand what it entails and be capable of having the unpleasant discussions that inevitably come with overseeing a crew. If you avoid having that tough conversation with a poor performer, you will have trouble managing a crew — it’s that simple. The following insights can help you manage your employees with just as much skill and intention as you manage your turf, fostering a more efficient operation and, ultimately, a better product.

Assemble a top-notch team

In job interviews, superintendent candidates usually have no problem articulating how they’d effectively deal with non-performers, as well as how they’d motivate, train and hold accountable members of their staff. Our answers can be spot-on, but our actual execution may be nonexistent.

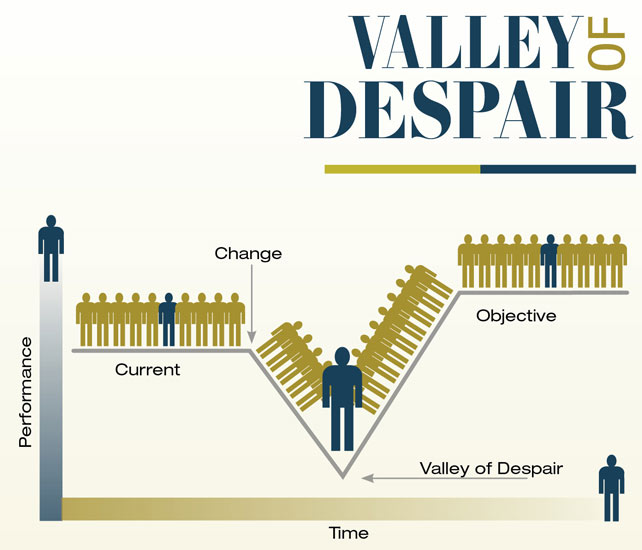

Even good managers tend to hang on to unsatisfactory performers simply because doing so is easier than coping with change. The “Valley of Despair,” as I call it, refers to that time immediately after you make a change, during which you experience a reduction in the overall performance of your operation. Recognize that this will only be a temporary drop, though, and that you will almost always come out on the other side with heightened efficiency. The majority of the time, after superintendents who have struggled with a co-worker finally make an adjustment, I’ll hear them say, “Why didn’t I do that a long time ago?”

Coupled with the fear of the Valley of Despair is the uncertainty surrounding available employees. Times have changed, and the days when you could post an ad online and fill an open position quickly are long gone. Great co-workers don’t come knocking on your door — you must go find them. To ensure you reach multiple qualified applicants, cast a wide net. Possible avenues to pursue include:

- Websites (Craigslist, Monster, Snagajob and ZipRecruiter, to name a few)

- Referrals from current employees or vendor

- Customers (consider placing business cards next to the register that offer free golf as an incentive for leads on standout employees)

- Signs and banners around the property (these attract people who live near your course)

- Community colleges, vocational schools and high schools

- Newspapers

- Nurseries and landscaping companies

- Other superintendents (some of their crew may be looking for part-time work)

- Bulletin boards around town where you can post the job announcement

The hiring process is always difficult. Some people are just good at answering questions, while others may stumble through the entire exchange. Your responsibility as an interviewer is to discern how a potential candidate would actually perform in the role. The person who seems to stumble through the conversation may in fact be a better fit than the person who has all the right responses. The book “Hiring Smart!” by Pierre Mornell is a must-read for anyone who conducts job interviews. It details many best practices you’ll find useful throughout the process, from the initial phone interview to making the final decision to hire. (It’s also a great read to prepare yourself for when you’re in the job candidate role.)

In the book “Jack Welch and the GE Way,” Welch, former CEO of General Electric, describes the exercise of listing each member of one’s workforce as either an A, B or C player. “A” players are the best of the best, and “B” players are working toward becoming A players. “C” players are all the others, and according to Welch, there’s no room in his company for C players. Building an A team is an ongoing effort, and the strategy of regularly addressing the under- or non-performing C players will not only improve their performance, but will be appreciated by your A and B players.

A variation on that idea is to “force-rank” your crew. First, make a list of your whole staff, and then determine who your No. 1 asset is — who you absolutely couldn’t do without. This may be an assistant or mechanic, or, in some cases, just a longtime co-worker who exemplifies a great work ethic. Next, determine your No. 2 person, and so on, inventorying your entire staff all the way through the person on your team you’d unfortunately consider the least valuable. You can then have a discussion with the people who ended up low on the list. As Welch puts it, “The biggest cowards are managers who don’t let people know where they stand.” Let those toward the bottom of your list know that you expect them to do better, otherwise consequences may be forthcoming. Monitor improvements, and make a change if necessary — that’s the only way to build a truly productive team.

This process is no doubt fraught with emotion as well as ideological and practical barriers that can stifle action. Personal connections sometimes come into play, and confronting veteran employees who have perhaps made notable contributions to the company in the past is especially daunting. I get it — it’s hard. But using these hurdles as excuses for not taking action will only result in continued average performance, and average performance is only acceptable if your goal is an average golf course.

Create a culture of accountability

“Inspect what you expect.” It’s a simple saying but a major component of performance management. If you’re not out on the course looking for low plugs on the greens, making sure tee markers are aligned correctly, watching the crew rake bunkers, and in general inspecting whether the standards you’ve set are being met, many everyday duties can end up being carried out inadequately. Establishing a straightforward, regular work-inspection protocol will eliminate much frustration and actually send a positive message to your staff — that you are interested in their work and want to help them succeed.

For those co-workers already doing a stand-up job, surveying their work will give you the opportunity to offer praise and reward. For those who need occasional feedback, inspection from you will help them grasp the importance of the tasks they’ve been assigned. And for the chronic offenders, your evaluation will signal to them that poor performance comes with consequences, whatever those may be. By inspecting what you expect, you can expect to see improvements.

Tap into motivation

As Dwight D. Eisenhower said, “Motivation is the art of getting people to do what you want them to do because they want to do it.” Understanding what motivates workers is a vital part of building a hardworking team. The work in and of itself may often be the motivation — I know that motivates me. Yet recognition, earning additional responsibilities, and the prospect of advancement within the company may also be driving forces. Ask your players what motivates them, and whenever possible, seek to accommodate their wishes.

Engaging your stakeholders in determining processes and systems can help them further buy in and see that they are a critical part of the operation. Keep them involved — empowerment can result in loyalty and a tremendous amount of energy.

Another strategy to spark motivation is to reward good behavior on an individual basis. Although this may seem obvious, it’s not a built-in part of every superintendent’s approach. Many times, perks for staff come in the form of barbecues, golf events and other occasions that acknowledge the team as a whole. This tactic rewards your C players just as much as it does your top crew member. There’s nothing wrong with singling out exceptional performers and rewarding them in front of their co-workers. Doing so makes it known that quality work gets rewarded, and others will likely want to reap such benefits.

Be clear, and be timely

Another valuable resource, particularly for new superintendents, is “The One Minute Manager” by Kenneth Blanchard, Ph.D., and Spencer Johnson, M.D., which guides readers through three principles crucial to managing people. The first of those is to set goals and make sure your staff knows exactly what’s expected of them. In golf course maintenance, goal setting usually comes via training or detailing a task and the expectations for the completed assignment. The concept may seem basic, but this is a step that can’t be overlooked, as it’s impossible to hold someone accountable for a job that is not entirely and clearly defined.

During a training session several years ago, an assistant superintendent said to me, “It seems like you’re trying to get co-workers to perform the job the exact way you would, and that will never happen.” In the assistant’s eyes, because I was the superintendent, I would inherently carry out the job to a higher standard than any other employee. I quickly corrected him and let him know that was precisely the goal — that each and every job on the golf course should be done to the quality that the superintendent would do it.

Blanchard and Spencer’s second “secret” is one-minute praise. They write, “Help people reach their full potential. Catch them doing something right.” What a pleasant thought compared with the flip side. If recognition is rare and warnings and threats are the norm, staff will work with anxiety and apprehension, which isn’t a formula for a happy, sustainable workforce.

The final practice is the one-minute reprimand, in which a manager immediately corrects poor performance and specifies the proper behavior, but does so in a way that conveys to the person that he or she is a valued team member. Timeliness with these latter two strategies is paramount. Praising employees for a job well done days or weeks after the fact will have little resonance. This immediacy also comes into play with holding employees accountable, as unchecked poor performance can quickly become the norm. Imagine driving by your fairway mower and seeing the operator sipping a cold beer. If you don’t swiftly step in to correct the misbehavior, it will be perceived as permissible. (In fact, next time, he’ll bring more beer!) Before you know it, you may find numerous tasks around the property being executed insufficiently, and trying to hit the reset button after months of things being done a certain way is incredibly difficult and inefficient. Always act promptly in giving both praise and corrections.

There are obviously HR issues to consider when addressing non-performers, and to list them all would be to expand this article into a book, so I’ll just say this: If you don’t have an HR department to help you navigate such situations, make sure you go through the documentation process we’re all familiar with: verbal and written warnings, performance improvement plans, and any other form of documentation that would show you did everything to counsel the co-worker and communicate ramifications. Ultimately, the actions you’re taking are designed to clarify expectations as a means of boosting performance. Often, just the process of putting these things down on paper and having the employee sign it is enough to shift behavior. In worst-case scenarios, when performance does not improve, the documentation becomes validation for change.

Stick to it

Now, take out your highlighter and highlight these next couple of sentences: All you need to do as a manager is identify the behaviors that are producing poor outcomes, and arrange consequences that will stop them. Likewise, you should identify behaviors that produce desirable outcomes, and arrange consequences that will reinforce them. (You can stop highlighting here, but read that over and over again until you have it memorized.)

Mindful management of your crew needs to be part of your to-do list every single day. It’s kind of like green speed — you can’t dial it up one week and then back the next. Make sure your staff has clear goals, hold them accountable, motivate them, find creative ways to recognize your best players (bearing in mind that monetary incentives do not keep talent if the work culture is negative), and address both poor and exceptional performance immediately. I’ll sometimes hear superintendents lament over subpar performers, “I have trained them several times on that. I don’t know why they don’t do it correctly.” My response is always the same: Any crew is only as good as its leader. If your crew members are doing an unsatisfactory job, it’s on you — nobody else.

To be clear, the takeaway from this article is a call to action. Although we’ve covered some of the hows and whys, my hope is that it prompts you to take a closer look at your team and take the steps required to strengthen it. If you have even an inkling that you’re getting less-than-acceptable production from your staff, you likely have something you need to address. Don’t try to dodge the Valley of Despair or sing the “I can’t find anybody better” blues — do what is necessary now to build the best team possible. The golf course will thank you for it.

Dave Waymire, CGCS, is a regional agronomist for American Golf Corp., where he has worked for 18 years. A 36-year member of GCSAA, Dave earned a two-year turf management certificate from Penn State University and has been a certified superintendent since 1993. He and his wife, Shelly, live in San Diego.