Figure 1. Annual bluegrass weevil adult and larva (right; photo, D. Shetlar), and larval damage (left; photo, S. Wu) in 2024.

The annual bluegrass weevil (ABW) has become a serious pest of low-cut turfgrass across the northeastern U.S. and adjacent Canadian provinces. Being first confirmed in the 1950s in New England, their geographical range of occurrence has been expanding, extending to Midwest and southern states, which was suspected to be associated with sod transportation (5). Golf course superintendents in northeastern states have been dealing with this pest for decades. However, in the newly established areas, turf managers’ knowledge about this pest and management strategies is rather limited. In Ohio, the ABW was first found in 2007 in northeastern regions and has been spreading to central and southern parts of the state. In recent years, there have been increasing reports about this pest’s damage (Figure 1), and superintendents have been looking for information for managing this pest problem.

To better understand the pest situations in Ohio, we conducted a survey on ABW distribution, management practices, insecticide applications and challenges faced. The survey was created on Qualtrics and distributed via Ohio Turfgrass Foundations, Ohio GCSA, Northern Ohio GCSA and Greater Cincinnati GCSA, as well as extension events in 2024. All responses were recorded anonymously, limited to one response per site, and the counties listed were used to plot out maps of ABW presence across Ohio.

Distribution and movement

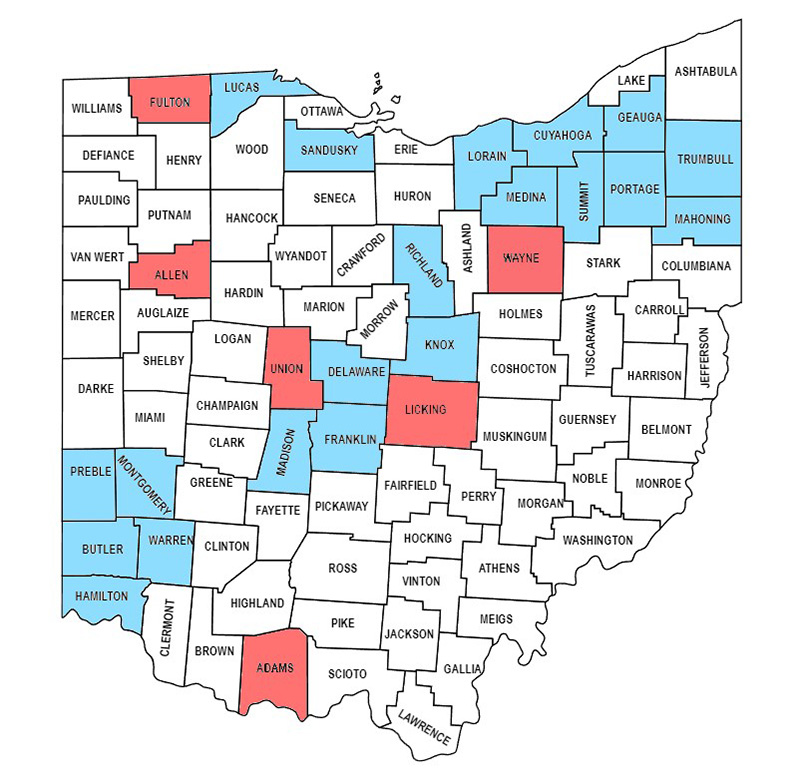

Figure 2. A map displaying presence and absence of annual bluegrass weevil in Ohio counties, where blue shading indicates ABW presence, red shading corresponds to ABW absence and white meaning no responses were received and ABW status was unknown.

We received responses from 75 participants across the state, mapped in county levels. Among them, 60 participants (80%) reported ABW populations on their courses, mostly clustering around Cincinnati, Columbus and Cleveland areas (Figure 2). The presence or absence of ABW is unknown in some regions (white color) due to lack of responses. This map demonstrates a clear picture of ABW movement through the state. Multiple reports of ABW presence were toward the Cleveland area (Northeast Ohio), where ABW was first reported in Ohio and has spread from. Following the survey, there have been more reports of ABW in central and southern Ohio.

Among the 60 sites that reported to have ABW, only 8% had significant damage, 65% with mild damage and 27% without damage. Considering the possibility of sod movement spreading ABW populations, the questionnaire asked whether these sites purchased sod before ABW occurrence. Among them, 40% reported to have bought sod from local producers in Ohio, 6% purchased sod from northeastern states and 6% from other states, while 48% had not purchased sod within the last five years prior to ABW occurrence. This suggests that sod transportation may account for ABW movement, but other pathways could have been involved, for example, maintenance equipment, traffic, etc. Also, in warm conditions, ABW adults can fly for short distances and may move by hitchhiking. There is also a possibility that ABW was present in turf but did not cause damage or was misdiagnosed as disease or environmental stresses, and thus the pest had been unnoticed until recently.

Host plants

Historically, the ABW was thought to only feed on annual bluegrass (Poa annua), after which it was named. There have even been attempts to use these weevils as “biological control” to remove Poa where it’s considered a weed in short-mown turf with other turfgrasses (e.g., creeping bentgrass, Agrostis stolonifera) as the predominant species. However, recently there are increasing reports of ABW damage on creeping bentgrass, especially in midwestern and southern states where Poa is scarce. In most regions, the ABW still appears to prefer Poa as the primary host and infests bentgrass secondarily, while it is common to have mixtures of Poa and bentgrass as low-cut turf in cool-season zones.

Among the 60 sites reporting to have ABW, 62% had infestation on Poa, 3% on creeping bentgrass, 32% on both turfgrasses and 3% of respondents were unsure which grass species was infested. This further supports that ABW prefers Poa but could also damage bentgrass.

Mowing

Management practices such as mowing and pest scouting may also affect ABW populations. In our previous studies (4), mowing could remove 24% of ABW adults from greens with a brush attached (versus only 0.5% in fairways) and 70% of those weevils were alive and undamaged, suggesting that most of them could survive the mowing. This indicates that collecting mowing clippings could remove a portion of weevils from greens; however, if clippings are dumped nearby, the surviving weevils could make their way back or re-infest the low-cut areas.

Among the sites reporting to have ABW, the majority of courses (91%) collected mowing clippings from greens, with 62% dumping clippings near the playing surfaces and 29% disposing of clippings away from the courses. However, none of the participants reported processing their grass clippings to kill ABW, suggesting the weevils may re-infest the courses.

Chemical control

In ABW heavily infested areas, insecticides are often sprayed to protect turf from their damage. This weevil has been considered difficult to control, due to its multiple-generation (usually 2-3 depending on locations) life cycle combined with asynchronous and overlapping developmental stages as the season progresses. Multiple insecticide applications are often made to manage the pest, and repeated applications without effective chemical rotations can lead to resistance development and control failures (3). Insecticide resistance in ABW has been confirmed in northeastern states, especially with pyrethroids, as well as several other insecticide classes but at lower levels (1, 2). In the new areas of ABW establishment, insecticide resistance may be of less concern as insecticides have not been heavily applied to control this pest, but the weevils may have already had resistance developed prior to relocation. Nonetheless, timing and number of applications, insecticide options and targeting stages are critical for control success.

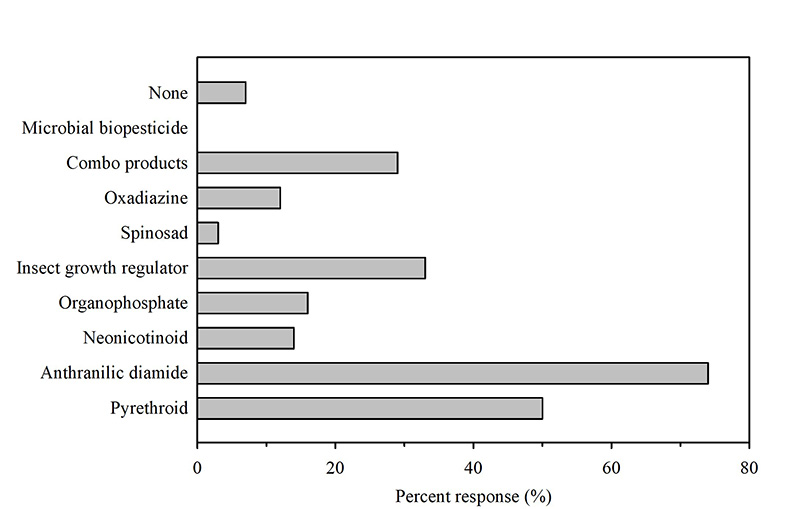

In this survey, the top three insecticide options (multiple choices) are anthranilic diamides (74%), pyrethroids (50%) and insect growth regulators (33%) (Figure 3). None of the sites reported to have used microbial biopesticides (based on nematodes/fungi) for biological control, indicating a need for more education and research on this front. Among the sites with ABW, 40% of courses only applied insecticides once or twice; 54% conducted three or four applications; and 6% sprayed five or more times per year. Most of these applications (87%) targeted both adult and larval ABW, 11% targeting larvae only and 2% against adults only.

Scouting for ABW stages and population densities could assist in determining the timing of insecticide applications and optimize the control efficacy. In this survey, a total of 44 participants (82%) performed some form of scouting for ABW populations (7% for larvae, 19% for adults, 56% for both) before their insecticide applications, helping them to best time their applications based on ABW life stages and population densities.

Figure 3. Percentage of survey participants that reported using the listed insecticides to manage annual bluegrass weevil populations (with multiple choices).

Overall, 65% of participants reported successful management of their ABW populations, 18% needed guidance in choosing insecticides, 32% requested guidance in timing their insecticide applications and 5% suspected insecticide resistance in ABW control (with multiple choices). This suggests there are still necessities of extension education and activities in assisting superintendents with ABW management.

Conclusions

This survey helps us to assess the scenarios of ABW problems in Ohio and identify the needs of stakeholders in managing this important pest. While some superintendents are able to successfully control ABW problems, improvements can yet be made to the management programs, especially in areas where the pest is new and information is inadequate. For best management practices, we suggest scouting for ABW stages and population densities for timely and threshold-based application of insecticides, rotating insecticides with different modes of action to slow resistance buildup and integrating cultural (e.g., collecting and processing clippings in green) and biological control with chemical approaches for effective and sustainable control of ABW populations.

The research says

- Among 75 participants across the state, 80% reported ABW populations on their courses, mostly clustering around Cincinnati, Columbus and Cleveland areas.

- The ABW prefers Poa but could also secondarily damage bentgrass.

- Sod transportation may account for ABW spreading, while other pathways may have been involved.

- The majority of courses (91%) with ABW collected mowing clippings from greens, with 62% dumping clippings near the playing surfaces; the weevils may survive mowing and re-infect low-cut turf nearby.

- Scouting for ABW stages and population densities could optimize the timing of insecticide applications and control efficacy.

- Rotating insecticides will help slow resistance development and improve management efficacy.

Literature cited

- Koppenhöfer, A.M., O.S. Kostromytska and S. Wu. 2018. Pyrethroid-resistance level affects performance of larvicides and adulticides from different insecticide classes in populations of Listronotus maculicollis (Coleoptera: Curculionidae). Journal of Economic Entomology 111(4):1851-1859. (https://doi.org/10.1093/jee/toy142).

- Kostromytska, O.S., S. Wu and A.M. Koppenhӧfer. 2018. Cross-resistance patterns to insecticides of several chemical classes among Listronotus maculicollis (Coleoptera: Curculionidae) populations with different levels of resistance to pyrethroids. Journal of Economic Entomology 111(1):391-392. (https://doi.org/10.1093/jee/tox345).

- McGraw, B.A., and A.M. Koppenhöfer. 2017. A survey of regional trends in annual bluegrass weevil (Coleoptera: Curculionidae) management on golf courses in Eastern North America. Journal of Integrated Pest Management. 8(1), p.2. (https://doi.org/10.1093/jipm/pmw014).

- Sousa, A.L.V., O.S. Kostromytska, S. Wu and A.M. Koppenhöfer. 2023. Optimizing sampling technique parameters for increased precision and practicality in annual bluegrass weevil population monitoring. Insects 14(6):509. (https://doi.org/10.3390/insects14060509).

- Vittum, P.J., 2020. Annual bluegrass weevil. In: Turfgrass insects of the United States and Canada, third ed. Cornell University Press, Ithaca, N.Y. pp. 284-298.

Dr. Shaohui Wu (wu.6229@osu.edu) is an assistant professor of Turfgrass Health in the Departments of Entomology and Plant Pathology at The Ohio State University, Columbus; Shane Moran and Henry Rice are graduate students in Dr. Wu’s lab.