Shade is often a limiting factor for some turfgrass species, while certain groundcovers thrive in the same exposure. Photos by John Fech

There are lots of locations on a golf course where turf just won’t grow well — too much shade, steep slopes and narrow spaces are just a few.

Installing groundcovers might be the solution to some of these challenges. Of course, they’re not maintenance free, but considering various options of better-adapted plants can improve the appearance and function of the course.

Ground cover options on a slope

Challenging locations

Shade. Trees, shrubs and buildings can cast light to heavy shade on various golfscape spaces. Though some turf species and cultivars can be fairly shade tolerant, many groundcover species provide color, texture and massing that is appealing and functional when turf is not. Of course, you can’t hit a golf ball out of a groundcover planting; many installations would be considered out of bounds, while others couldn’t handle the divots. But, if something green is needed and the choice is between thin, struggling Kentucky bluegrass or bermudagrass and periwinkle or carpet bugle, the groundcovers will win most every time.

Small and oddly shaped locations on the golf course are sometimes best suited for a groundcover.

Slopes. Safety is a big issue when mowing on a slope. Using an adapted groundcover that doesn’t need mowing decreases the chance of an accident while reducing erosion and retaining aesthetic appeal. Irrigation on slopes is a definite challenge, even for groundcovers. Some species need to be kept moist, while others can get by on very little moisture. The most critical times for delivering water to plants on a slope are during establishment and when natural precipitation is less than adequate.

Narrow/small spaces. Turfgrass plants are difficult to manage when they are in spaces that are long and less than 3 feet wide. Most, if not all, of the cultural practices, such as irrigation, aeration, fertilization and pest control, are much more readily implemented in areas that are larger and/or wider. In some situations, groundcovers are a good alternative in these spots (aka islands), as they tend to be easier to water and fertilize than narrow strips of turf. If the soil is properly prepared before planting, aeration is called for less frequently. No plant choice is perfect; however, groundcovers can be susceptible to as many, but different, pest infestations as turfgrass.

The specifics of a particular space are important considerations for any golfscape space.

Evaluate the site

Just as it is for various turf species/cultivars, the analysis of the planting site is paramount to success. Knowing the sun/shade exposure, soil drainage capacity, air circulation patterns and cold/heat extremes, as well as the optimal height for the plant material, will help create a short list of suitable plants. These specifics of the space can then be matched with the attributes of each plant choice. Assistance from a university horticulturist or golf course architect can be invaluable as sites are assessed for various facets of microclimate.

Desirable plant features

When interviewing candidates for a job, search industry experts suggest asking yourself, “What do I get with this person?” The same is true for picking out groundcovers. Using information gathered about the site, the plant-specific attributes of leaf color, flower color, growth habit, height, disease susceptibility, seasonal appeal features, and ease of care can be matched together for a suitable selection. Overall, the tried-and-true approach of Right Plant, Right Place is highly effective, as it combines these two realms: the specifics of the site and the plant.

Aesthetic appeal, no matter how subtle, greatly adds value to the golfscape.

Establishment

Soil amendment. As mentioned earlier, you generally only get one shot at creating a root zone with the desirable amount of humus/organic matter, air space between soil particles and pH. Since it’s not appropriate to aerate groundcover plantings, it’s best to start off at planting time with everything that is needed.

As a rule with ornamentals, when we consider woody plants, it’s not practical to amend planting sites, (in fact, it can be detrimental, as roots tend to grow preferentially in modified soils), but with herbaceous plants, generally it is. This yes/no tenet is based on the feasibility of modifying the entirety of the eventual root system of the plant. Amending/improving the whole root system of a medium-sized tree is a huge undertaking. However, since a groundcover plant has a much smaller root system, even in a planting bed, amending the soil according to the results of a soil test is much more achievable. As with other ornamentals, the pH, organic matter content, cation exchange capacity and various essential nutrients are the ones to consider.

Proper spacing is critical in a successful ornamental area.

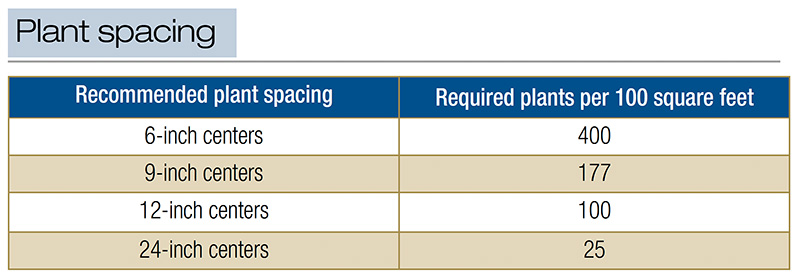

Spacing. Proper spacing is a crucial factor in the success of a groundcover planting. Plants spaced too close together are likely to crowd each other, compete for water and nutrients, and create a dense canopy that encourages the development of foliar diseases. Plants spaced too far apart often lack the visual appeal necessary to create a pleasing mass and leave open space for weeds to grow. Plant care tag information is helpful in this regard; the chart on this page is also a good general guide.

If the “new plant budget” is a little on the thin side, consider the 9-inch spacing; utilizing it will produce a fairly rapid coverage of the area with less than half the number required for a 6-inch spacing.

Wood chip mulch and judicious use of pre-emergence herbicides are good tools for preventing weed competition.

Weed control. Yes, pathogens and insects are problems when establishing groundcovers, but the No. 1 problem is annual and perennial weeds. Naturally, this makes sense when you consider that our soil science/weed science colleagues tell us that the average cubic foot of soil has about 10,000 weed seeds in it. When the soil is disturbed during planting, many of these are brought to the surface; later, when they are watered and fertilized, they are encouraged to grow, especially in the presence of sunlight. Two inches of wood chip or pine needle mulch and appropriate preemergence herbicides go a long way toward preventing germination and growth of unwanted plants.

Irrigation. Depending on the preferred moisture level of the plants being established, both temporary and permanent systems are valuable. Most, but not all, groundcovers need moist, not soggy or dry soil in contact with the roots in order to develop sufficiently. For some, overhead micro spray heads work well; drip irrigation emitters are best for others. Much of the decision on irrigation system specifics depends on the height of the plant material and the slope of the space.

For some ornamentals, overhead micro spray heads work well; drip irrigation emitters are best for others.

Fertilization. Successful establishment of groundcovers is usually influenced greatly by the development of balanced growth of the roots and shoots, leaning slightly more importantly toward the roots. Sure, leaves photosynthesize and make sugars and carbohydrates, but without healthy roots, the shoots quickly go away. As such, the fertilization schedule in the first year should be geared toward root growth, in accordance with soil test results. Incorporation of compost in the context of organic matter content is usually beneficial in provision of nutrients, facilitating drainage and rapid root expansion.

Pruning

After the first year of growth, some groundcovers will need to be thinned, pruned or simply restricted in the growth horizontally. The concept is to solve the problem but not create one by allowing them to creep into spaces where other plants are currently serving a valuable purpose. Generally, the woodier that a groundcover is, the more effort that this entails. Keeping pruning needs in mind when selecting a species is a valuable consideration, as available labor can be limited in some situations.

Overall, groundcovers are not a panacea. They’re simply a good option for certain spaces where turfgrass and woody plants are not a good choice. Evaluating the site, considering the time needed to keep them looking good and functioning well, making a wise choice of available options and providing the weed control, fertilization and irrigation necessary to get them off to a good start will help them become a positive part of the golfscape.

John C. Fech is a horticulturist and Extension educator with the University of Nebraska-Lincoln. He is a frequent and award-winning contributor to GCM.