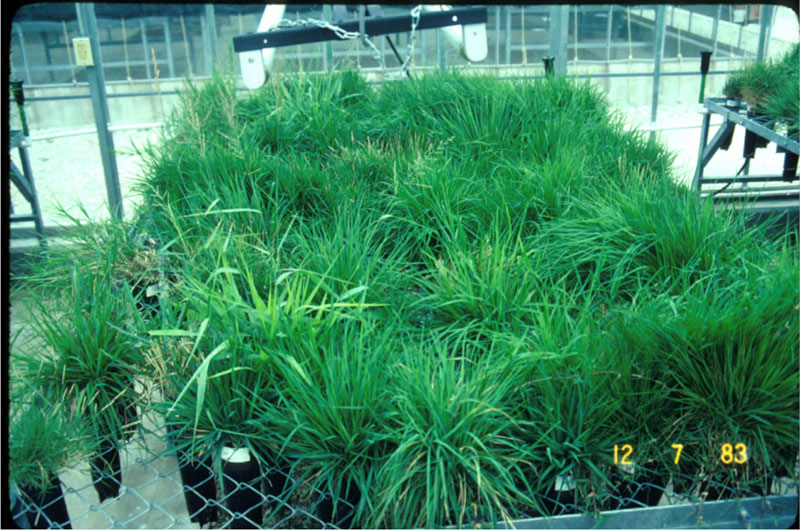

A look inside Milt Engelke’s nursery of unique zoysiagrasses back in 1983. Photos courtesy of Milt Engelke

Editor’s note: In conjunction with “Zoysia and the Future of Golf: Fewer Inputs from Tee to Green,” a learning tour at the 2018 Golf Industry Show in San Antonio, GCMOnline.com is presenting a series of stories on zoysiagrass, its increasing prominence in golf, and the learning tour itself, provided by Team Zoysia.

In 1982, the late Jack Murray and I embarked on a germplasm collection trip to the center of origin for a relatively minor, albeit important turfgrass species known only as “zoysia.” The collection of zoysiagrasses — or scientifically known as “plant accessions” (plant materials that have unique physical characteristics) — that Jack and I gathered in 1982 in our travels through Japan, Korea, Taiwan and the Philippines became important to our respective breeding and turfgrass development programs — Jack with the USDA in Beltsville, Md., and me with Texas Agricultural Experiment Station (now Texas A&M AgriLife Research) in Dallas.

Over the years, we individually and collectively amassed additional plant collections through more travels (1985, 1987, 1992, 1995, 2005) and personal connections with international scientists. The collection totaled more than 1,200 unique plants by the time of my retirement in 2010. I committed to maintaining this diverse collection (i.e., germplasm nursery) of unique zoysiagrasses in isolation under greenhouse conditions beginning in 1983. What we didn’t necessarily realize at the time was how fragile the system of the origin of the species had become, primarily because of industrialization of the region (Asia-Pacific) and urbanization of the planet.

For example, one of the outstanding features of the 1982 trip was the opportunity to collect plant materials from the royal tombs in the Republic of Korea (South Korea), which dated back to 1200 A.D. (right). These tombs are scattered throughout Korea not only in honor of the legacy of kings, but also in public cemeteries, where zoysiagrass is used to stabilize the soil mounded over the aboveground burial sites. Selected as much for its winter color (golden), zoysiagrass also provided stability for the aboveground tombs with minimal maintenance.

For example, one of the outstanding features of the 1982 trip was the opportunity to collect plant materials from the royal tombs in the Republic of Korea (South Korea), which dated back to 1200 A.D. (right). These tombs are scattered throughout Korea not only in honor of the legacy of kings, but also in public cemeteries, where zoysiagrass is used to stabilize the soil mounded over the aboveground burial sites. Selected as much for its winter color (golden), zoysiagrass also provided stability for the aboveground tombs with minimal maintenance.

What was striking was the plant’s ability to adapt to what we like to think of today as “sustainable,” with minimal inputs. This site is more than 800 years old. It is not subjected to the rigors of lawn maintenance we know today. No fertilizer, organic or synthetic. Only natural rainfall, which may reach as much as 40 to 50 inches annually but generally occurs in a six-month period, with the balance of the year being virtually drought-ridden. No mowers allowed — not even hover mowers — dating back to the tomb’s origin. The biology of these plants provides excellent erosion control, and they are drought-tolerant and sustainable with minimal (basically no) maintenance — no weed control, no mowing, no fertilization, no irrigation, and no need for pest control.

What was fragile about this system was realized on the trip David Doguet of Bladerunner Farms and I just returned from, where we again had the opportunity to visit a different set of royal tombs, and where, to my surprise, a major resodding of the site was underway (above). Resodding of the site! We thought this site was sacred. So much for the 800-year legacy. This put further emphasis on the fragility of the system. Advances in modern social presentations, even in Korea, apparently demanded the site be “rebuilt,” much like our golf courses need to be rebuilt every few years. The situation is now similar to the loss of our native prairies in the United States.

The Republic of Korea was a much different country in 1982 when Jack and I made our first trip. We often found water buffalo — beasts of burden — being used for plowing rice fields on one farm, while the next farm was using modern industrial machinery. Korea was in its infancy of the industrial revolution then. Today, it is a powerhouse.

On that trip, we visited the sea coast region of Incheon, north and west of Seoul, South Korea, and bordering the Yellow Sea. A widespread practice to support the country’s economy was to harvest salts from the sea by evaporating sea water in salt beds. The salt beds amounted to structured dikes of soil in which the sea was allowed to fill, and which were then sealed off. Over time, evaporation concentrated the salts. The plants growing naturally on the edge of these dikes was a species of zoysiagrass that obviously had excellent salt tolerance. In this case, the plant was able to withstand high-saline soils far greater than anything we experience in our society. The fragility of the system is emphasized by further globalization and industrialization, which I realized in 2005 when I had the opportunity to return to South Korea and this time landed in one of the most modern airports in all of Asia, Incheon International Airport (right), which sits on the very site of those salt beds. To my dismay, I realized that those natural selections of the evolving salt-tolerant species were gone forever.

On that trip, we visited the sea coast region of Incheon, north and west of Seoul, South Korea, and bordering the Yellow Sea. A widespread practice to support the country’s economy was to harvest salts from the sea by evaporating sea water in salt beds. The salt beds amounted to structured dikes of soil in which the sea was allowed to fill, and which were then sealed off. Over time, evaporation concentrated the salts. The plants growing naturally on the edge of these dikes was a species of zoysiagrass that obviously had excellent salt tolerance. In this case, the plant was able to withstand high-saline soils far greater than anything we experience in our society. The fragility of the system is emphasized by further globalization and industrialization, which I realized in 2005 when I had the opportunity to return to South Korea and this time landed in one of the most modern airports in all of Asia, Incheon International Airport (right), which sits on the very site of those salt beds. To my dismay, I realized that those natural selections of the evolving salt-tolerant species were gone forever.

Expanded urbanization throughout Asia (Thailand, Vietnam, China, Korea) has the potential to negatively impact unique genetic resources. Many sites have been permanently disturbed, and the genetic diversity has been eliminated. Fortunately, scientists throughout the agricultural communities worldwide have recognized the loss of genetic diversity in many different species caused by urbanization and industrialization.

Several decades ago, a concerted effort was initiated to preserve many of these diverse resources through the development of germplasm repositories for the many different species. The collection that Jack and I started in 1982 was a first step in preserving zoysiagrass germplasm. The original genetic material is presently being maintained (at least as of 2010) at Texas A&M Dallas.

Jack retired from the USDA in 1988 and continued working with samples from his collection up until his untimely death in 1995. David and Sheri Doguet acquired his post-retirement collection just prior to his death. With it, they initiated the Bladerunner Farms research program, which you’ll have the opportunity to visit during the 2018 Golf Industry Show in San Antonio. During the tour, you’ll have the opportunity to meet Ambika Chandra, Ph.D., of Texas A&M AgriLife Research, and Brian Schwartz, Ph.D., of the University of Georgia-Tifton, the young turf breeders who are presently working with these collections. Many of these unique plants are being used for the development of new grasses for the future of the industry.

Many of the unique plants hold biological advantages not necessarily present in modern zoysiagrass varieties, but with the preservation of these genetically diverse plants, we can be assured access to their unique genetic features for years to come.

M.C. (Milt) Engelke, Ph.D., is professor emeritus at Texas A&M University.