An example of winterkill on a golf course putting green. Photo by Kevin Frank

Winterkill is defined as the loss of turfgrass in the winter months from stresses including freezing stress, winter desiccation and winter diseases (1). Winterkill can cause devasting loss to turfgrass on golf course putting greens (Picture 1). The winters of 2013-2014 were particularly devastating for the Great Lakes region, with most loss being observed on annual bluegrass putting greens (4). When widespread winterkill occurs, golf courses must remain closed in the spring to repair the damage. A recent economic study found that some golf courses that experienced considerable winterkill reported revenue losses greater than $75,000 (11). Due to these severe economic consequences, superintendents need to reestablish golf course putting greens quickly.

The most common method of reestablishing putting greens is with creeping bentgrass seed. Reestablishing with seed can be viewed as an opportunity to reintroduce creeping bentgrass in killed annual bluegrass voids (9). One major challenge of reestablishing with seed in the spring is the lack of suitable germination conditions, as optimal creeping bentgrass germination temperatures have been found to be around 77 F (25 C) (10). Relatively recent research in growth chambers has found that creeping bentgrass germinability varies among cultivars when grown at cooler temperatures (45 and 50 F/7.2 and 10 C) (2, 5). Of the cultivars tested, Crystal BlueLinks, Declaration, Penn A-4, Proclamation, Pure Select and 007 had the greatest germination in suboptimal temperatures (2, 5).

The objectives of this study were to evaluate the effects of three spring seeding dates and seven seed entries on spring establishment rate following simulated winterkill on an annual bluegrass putting green.

Annual bluegrass putting green following two sequential applications of glyphosate and diquat dibromide to simulate winterkill in East Lansing, Mich., April 2024. Photo by Payton Perkinson

Materials and methods

A field trial was conducted in 2023 and 2024 at the Hancock Turfgrass Research Center (HTRC), Michigan State University, East Lansing. The experiment was placed on an annual bluegrass native soil research putting green that had been sand capped from years of light and frequent sand topdressing. To simulate winterkill, glyphosate and diquat dibromide were applied to the putting green twice prior to treatment initiation on March 30 and April 20, 2023, and Oct. 18, 2023, and March 15, 2024. After the two herbicide applications, there was no visible green tissue remaining on the putting green (Picture 2). One half of the putting green was used in 2023, and the other half of the putting green was used in 2024 to reduce treatment effect from the creeping bentgrass that had established the prior year.

Treatments were arranged in a randomized complete block split-plot design. The whole plot (seeding date) included three treatments: seeding date one, seeding date two and seeding date three. Seeding date one was initiated when the daily average soil temperature at 2-inch depth was at 45 F. Seeding date two and three followed seven and 14 days after seeding date one, respectively. In 2023, seeding dates were April 14, April 21, April 28, and April 8, April 15, April 22, 2024. Within each seeding date, the subplot (seed entry) included seven treatments: creeping bentgrass cultivars Penn A-4, Declaration, Penncross, Pure Distinction, Two-Putt annual bluegrass, a 50/50 by weight mixture of Pure Distinction and Two-Putt, and a non-seeded control.

On each seeding date, the plots were verticut in two opposite directions at a depth of 0.15 inch (0.38 centimeter) using a walk mower with a vertical mower attachment (0.4-inch/1 centimeter blade spacing) to encourage soil-to-seed contact. Any remaining debris on the putting green was removed with backpack blower. Seed was applied by hand shaker bottles in multiple directions at a rate of 2 pounds seed per 1,000 square feet (9.76 grams per square meter). Starter fertilizer was applied at a rate of 1 pound phosphorus per 1,000 square feet (4.88 grams per square meter), and a layer of sand topdressing at a rate of 115 pounds per 1,000 square feet (561 grams per square meter) was applied over the putting green to encourage seed incorporation.

During establishment, plots were irrigated with overhead irrigation to provide adequate germination. Nitrogen as urea (46% nitrogen-0% phosphorus-0% potassium) was applied at a rate of 0.2 pounds nitrogen per 1,000 square feet (0.98 grams per square meter) every two weeks after the first seedling emergence was observed. Plots were mowed three times a week with a reel walk mower starting at May 22, 2023, and May 17, 2024, at height of cut of 0.25 inch (0.64 centimeter) and gradually dropped to 0.1 inch (0.25 centimeter) over the course of four weeks during the establishment period.

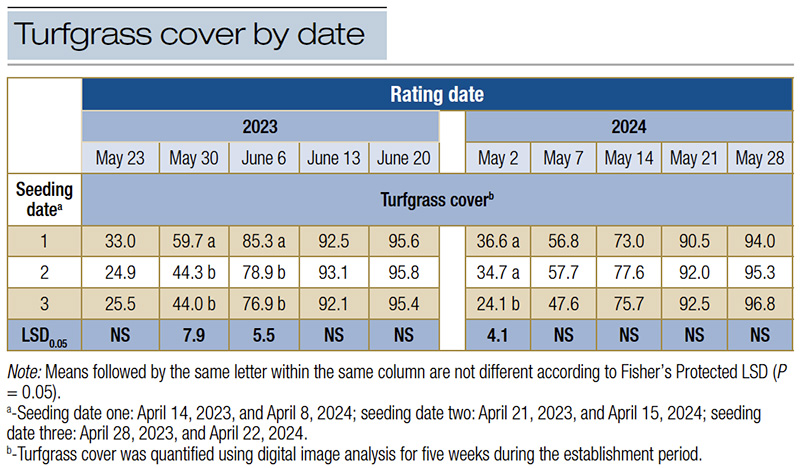

Table 1. Turfgrass cover (%) in response to seeding date on five rating dates in 2023 and 2024 in East Lansing, Mich.

Data collection and statistical analysis

Turfgrass cover was assessed using digital image analysis weekly for five weeks after seeding beginning approximately one month after seeding date one. A light box was placed in the center of each plot, and a single image was captured using a SONY RX100 VI camera. Images were then analyzed to assess turfgrass cover using ImageJ (8) and were configured to quantify the number of green pixels in the image.

Data from each year were analyzed separately through PROC GLIMMIX in SAS software (version 9.4; SAS Institute Inc.). Block was treated as a random effect and seeding date was nested within each block. Analysis of variance (ANOVA) was conducted on fixed effects of seeding date and seed entry to determine significant differences (P ≤ 0.05). Fisher’s least significant difference (LSD) was used when difference among treatment means occurred.

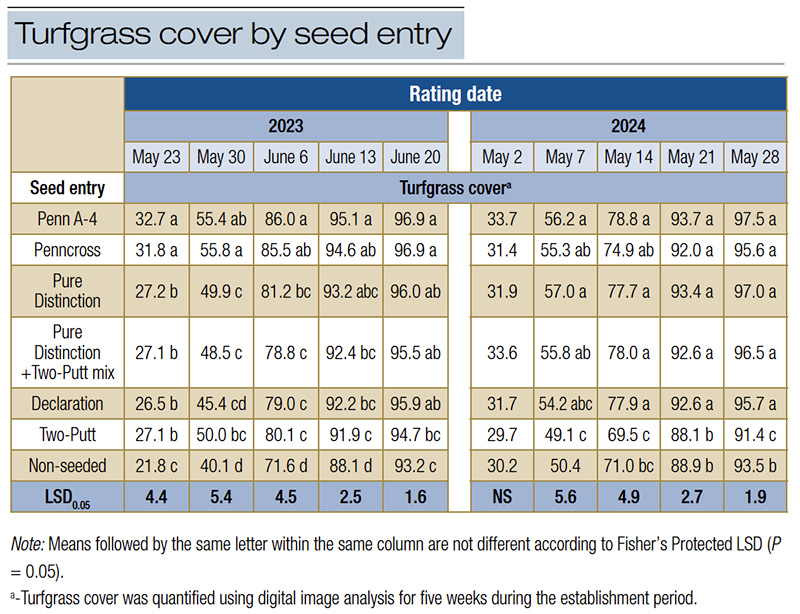

Table 2. Turfgrass cover (%) in response to seeding entry on five rating dates in 2023 and 2024 in East Lansing, Mich.

Results and discussion

Seeding date main effect

On May 30 and June 6, 2023, seeding date one had the highest percent turfgrass cover with 59.7% and 85.3%, respectively (Table 1). On May 2, 2024, seeding date one and two had higher turfgrass cover than date three. However, by the end of data collection in 2023 and 2024, there was no difference in turfgrass cover among treatments, and all three seeding dates averaged greater than 94%. These results suggest that an earlier seeding date may make a small difference on early spring establishment but would not enable a golf course to resume play on putting greens any sooner compared to a later seeding date. Yet there were no negative impacts observed from seeding earlier.

Seed entry main effect

On May 23, May 30 and June 6, 2023, Penn A-4 and Penncross had the highest turfgrass cover among all seed entries (Table 2). In previous growth chamber research, Penn A-4 was found to have some of the most consistent germination percentages in suboptimal temperatures (2), but Penncross has not been found to germinate exceptionally well at suboptimal temperatures (2, 5). In the present study, however, there was less than 10% difference in turfgrass cover among seed entries, excluding the non-seeded treatment. By the end of data collection, all entries, including the non-seed treatment, averaged greater than 93% of turfgrass cover.

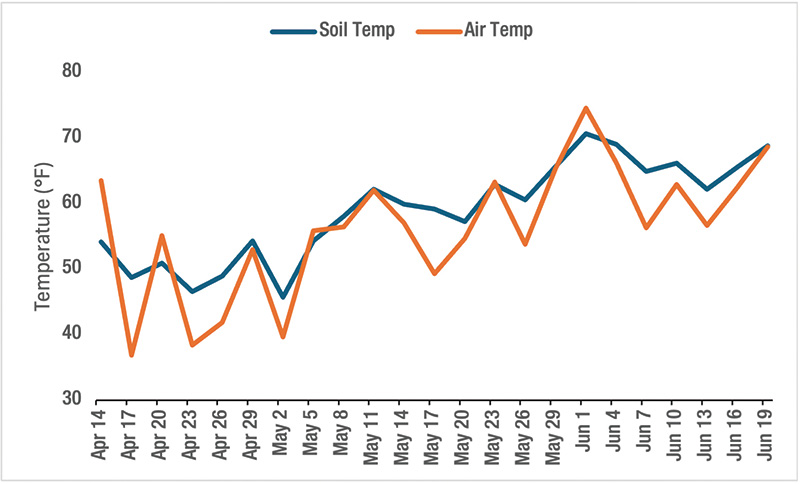

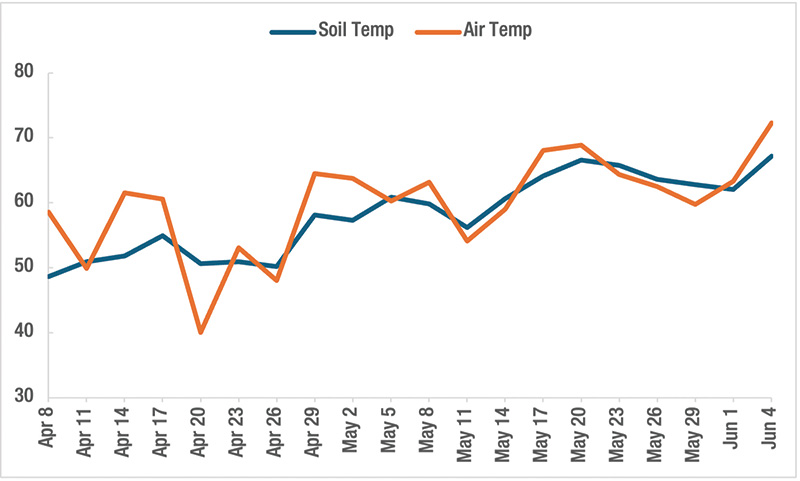

In 2024, all the creeping bentgrass entries, including the 50/50 Pure Distinction and Two-Putt annual bluegrass seed, were not different from each other at any point in the trial year. Two-Putt consistently had the lowest turfgrass cover among seed entries, excluding the non-seeded treatment. The lack of differences among creeping bentgrass cultivars in 2024 can be attributed to warmer spring temperatures (Figure 1).

In the first 21 days after seeding date one, soil temperatures averaged 51.1 F (10.6 C) in 2024 at a 2-inch (5-centimeter) depth compared to 50 F in 2023. In previous field-based spring establishment research, creeping bentgrass was found to emerge at approximately 50 F, and even small increases of 1.8 F (1 C) in soil at a 0.5-inch (1.27-centimeter) depth have been found to increase turfgrass cover (3). By the end of the study in both 2023 and 2024, the non-seeded control plots averaged 93% turfgrass cover. This is likely due to the emergence and establishment of annual bluegrass into these plots (6).

Figure 1. Daily average soil temperature at 2 inches and air temperature at the Hancock Turfgrass Research Center in East Lansing, Mich. (a). Daily average soil and air temperature from April 14 to June 20, 2023. (b). Daily average soil and air temperature from April 8 to June 4, 2024.

Conclusions

Results suggest that an earlier seeding date may make a small difference in turfgrass establishment rate, but differences would not allow a golf course to reopen earlier following winterkill. However, there were no negative effects observed from seeding earlier. Additionally, results from this study are similar to prior work that creeping bentgrass cultivars have variability in germination at cooler temperatures. In the present study, Penn A-4 and Penncross had the highest turfgrass cover at the beginning of data collection in 2023, but all seeded entries were less than 10% different from each other.

In 2024, all creeping bentgrass entries had similar turfgrass cover, likely due to the warmer temperatures. Two-Putt consistently performed poorly compared to the other entries. Annual bluegrass from the soil seed bank germinated and established in the non-seeded treatments, albeit at a slower rate than the other seed entries.

The research says

- Results suggest that an earlier seeding date may make a small difference in turfgrass establishment rate, but differences would not allow a golf course to re-open earlier following winterkill.

- Results from this study are similar to prior work that creeping bentgrass cultivars have variability in germination at cooler temperatures.

- Penn A-4 and Penncross had the highest turfgrass cover at the beginning of data collection in 2023, but all seeded entries were less than 10% different from each other.

- In 2024, all creeping bentgrass entries had similar turfgrass cover likely due to the warmer temperatures.

Acknowledgements

This research was supported by the U.S. Department of Agriculture, National Institute of Food and Agriculture, Specialty Crop Research Initiative under award number 2021-51181-35861. Any opinions, findings, conclusions or recommendations expressed in this publication are those of the author(s) and should not be construed to represent any official USDA or U.S. Government determination of policy.

This research summarizes findings previously reported by Perkinson & Frank (7).

Literature cited

- Beard, J.B., and Harriet J. Beard. 2005. Winterkill. p. 502. In: Beard's Encyclopedia for Golf Courses, Grounds, Lawns, Sports Fields. Michigan State University Press, East Lansing, Mich.

- Carroll, D.E., J.E. Kaminski and P.J. Landschoot. 2020. Creeping bentgrass seed germination in growth chambers at optimal and suboptimal temperatures. Crop, Forage & Turfgrass Management 6:e20068 (https://doi.org/10.1002/cft2.20068).

- Ebdon, J.S., and M. DaCosta. 2021. Soil temperature mediated seedling emergence and field establishment in bentgrass species and cultivars during spring in northeastern United States. HortTechnology 31(1):42-52 (https://doi.org/10.21273/HORTTECH04653-20).

- Frank, K. 2014. Turfgrass winterkill observations from the Great Lakes Region. Applied Turfgrass Science 11:1-4 ATS-201400057-BR (https://doi.org/10.2134/ATS-2014-0057-BR).

- Heineck, G.C., S.J. Bauer, M. Cavanaugh, A. Hollman, E. Watkins and B.P. Horgan. 2019. Variability of creeping bentgrass cultivar germinability as influenced by cold temperatures. Crop, Forage & Turfgrass Management 5:1-7 (https://doi.org/10.2134/cftm2018.07.0054).

- Kaminski, J.E., and P.H. Dernoeden. 2007. Seasonal Poa annua L. seedling emergence patterns in Maryland. Crop Science 47:775-779 (https://doi.org/10.2135/cropsci2006.03.0191).

- Perkinson, P.C., and K.W. Frank. 2025. Re-establishment of an annual bluegrass putting green following simulated winterkill. Crop, Forage & Turfgrass Management 11:e70066 (https://doi.org/10.1002/cft2.70066).

- Schneider, C.A., W.S. Rasband and K.W. Eliceiri. 2012. NIH Image to ImageJ: 25 years of image analysis. Nature Methods 9:671-675 (https://doi.org/10.1038/nmeth.2089).

- Stier, J. 2005. Take advantage of Poa annua winterkill: Increase bentgrass on putting greens. The Grass Roots 34(3):4-9.

- Toole, V.K., and E.J. Koch. 1977. Light and temperature controls of dormancy and germination in bentgrass seeds. Crop Science 17:806-811 (https://doi.org/10.2135/cropsci1977.0011183x001700050033x).

- Yue, C., U. Parasuram, E. Watkins, D. Soldat, P. Koch, K. Frank and M. DaCosta. 2025. The economic cost of winter injuries on golf courses in North America. HortScience 60(8):1389-1397 (https://doi.org/10.21273/HORTSCI18673-25).

Payton Perkinson, perkinso@msu.edu, is formerly a master’s student in turfgrass management at Michigan State and is currently a doctoral student in turfgrass management at North Carolina State University, Raleigh; Kevin Frank is a professor and turf Extension specialist at Michigan State.